Introduction

Secretions in the bronchial tree and tracheostomy or endotracheal tube (ETT) of ventilated patients impact the efficacy of ventilation.1 Side-effects of airway secretions include an increase in resistance to airflow and work of breathing,2 a decrease in ventilation of lung segments distal to blocked airways,3 and the development of atelectasis.4 Acute tracheostomy or ETT obstruction and sudden death can occur. Effective clearance of airway secretions is therefore essential in ventilatory management, and is usually achieved by catheter suction (CS). CS is an invasive procedure that is associated with hemodynamic side effects5 such as tachycardia and increased blood pressure, mucosal trauma,6–10 and an increased risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).11–14 CS is necessary because invasively ventilated patients cannot cough effectively to clear their airways.15

A noninvasive alternative to CS is mechanical insufflation-exsufflation (MIE), in which the airflow dynamics of a cough are simulated mechanically to move secretions up the respiratory tree by the kinetic energy imparted to the secretions by airflow.16,17 The technique dates back to the Polio epidemic of the 1950s, and comprises insufflating the lungs to a volume approaching the vital capacity of the lungs, followed by a rapid mechanical exsufflation (suction) of air out of the lungs, thus simulating a cough.18

As a non-invasive modality, MIE does not cause the invasive complications of CS. However, despite reports documenting the value of MIE in aiding progress to extubation in the ICU,19,20 and its common use in the context of chronic non-invasive ventilation,21,22 MIE devices remain largely unused as an alternative to CS in subjects on chronic ventilation via a tracheostomy or an ETT, as their use requires disconnecting the patient from the ventilator to connect the patient to the MIE device. This disrupts the patient’s ongoing ventilation, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), and administered oxygen (FiO2).

In-line mechanical insufflation-exsufflation (IL-MIE) is a new method for performing MIE in invasively ventilated patients in the ICU, which overcomes the drawbacks of MIE for ICU use.23,24 IL-MIE devices are integrated in-line with the patient’s ventilator circuit and do not themselves perform insufflations. Rather, the regular inspiration provided by the ventilator serves as the insufflation phase of each simulated cough, and the IL-MIE device performs only exsufflation, timing the onset of each exsufflation to the beginning of passive exhalation. Figure 1 demonstrates the setup and mode of operation of an IL-MIE device. Although the figure depicts the IL-MIE device as connected to an ETT, the setup and mode of operation are identical when the device is connected to a tracheostomy tube instead. The concept of IL-MIE was first developed by one of the authors (EB) in the Department of Respiratory Rehabilitation of ALYN Hospital in Jerusalem, Israel.25

The IL-MIE suction unit connects in-line with the patient’s ventilation circuit via a Y-connector positioned on the patient’s endotracheal tube (ETT), as pictured, or tracheostomy tube. The Y-connector contains a pneumatic valve that controls the direction of airflow: either from the ventilator to-and-from the patient (during inspiration and regular expiration), or from the patient to the IL-MIE suction unit (during exsufflation). The IL-MIE device activates the suction and the pneumatic valve only during expiration, based on pressure and flow inputs received from sensors in the Y-connector. The system is universally compatible with all ventilators and most modes of ventilation. Secretions mobilized from the airways accumulate in the Y- connector, or in a water trap, from where they are removed with a suction catheter (which does not traverse the ETT or tracheostomy tube or enter the patient’s airways).

The current study is the first reported use of an IL-MIE device as an elective alternative or adjunct to CS in the routine management of ventilated patients in the ICU. The hypothesis was that regular IL-MIE, with CS performed only as a backup if needed, is similar to a protocol of CS alone for primary airway clearance in mechanically ventilated patients.

Methods

Trial Design

The study was designed as a randomized, open-label, parallel, non-inferiority, controlled trial. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tiantan Hospital (approval number QX2015-010-02), and informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects, either prior to their surgical procedure or from an authorized relative after the surgical procedure. CONSORT reporting guidelines were used. The study was registered on the PRS database in ClinicalTrial.gov (ID: NCT05365620).

Participants

Participants included patients aged 18 to 75 years undergoing mechanical ventilation during the immediate recovery period following a cardiac or neuro-surgical procedure. Patients were excluded from the study if they had any theoretical contraindication to IL-MIE, such as acute spinal cord shock, recent airway trauma or surgery, cardiogenic pulmonary edema, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) necessitating ventilation with a high peak end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). Also excluded were patients with pneumothorax, hemoptysis, or severe ischemic heart disease. The study was conducted in two Intensive Care Units: Cardiac Surgery ICU at Anzhen Hospital and the Critical Care Medicine ICU at Tian Tan Hospital, both in Beijing, China.

Interventions

IL-MIE was performed using standard IL-MIE parameters (exsufflation pressure = -60 cm H2O, with flutter, 10 coughs/treatment). The CoughSync device does not require setting an exsufflation time, as the device terminates exsufflation automatically when expiratory airflow from the patient approaches zero, using a flow-cycled mechanism. CS was performed whenever deemed clinically indicated in the assessment of the treating nursing staff, according to the standard protocol for secretion management in the two participating ICUs, as described in Table 1.

Before each CS treatment, 100% oxygen was administered for one minute, regardless of the patient’s baseline oxygen requirement, as per the standard operating protocol in that ICU. Before IL-MIE treatments, no additional oxygen was administered beyond the patient’s baseline oxygen requirement. Pharmacological management in both groups included analgesia and sedation as routinely used postoperatively in those ICUs.

Outcomes

Demographic information and vital signs were recorded for all subjects. Arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), and oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2) were defined as the primary endpoints of the study, with arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2), pulse oximetry (SpO2), heart rate (HR), and ventilator parameters (inspired oxygen, tidal volume [Vt], peak inspiratory pressure [PIP], airway plateau pressure [Pplat], and PEEP) as secondary endpoints.

All primary and secondary endpoint data were recorded at baseline (2 minutes prior to starting the trial), and at 5 minutes, 4 hours, and 8 hours after the commencement of the trial. The number of CS treatments performed on each subject was recorded throughout the trial. Follow-up for adverse events was performed during and 48 hours after the completion of the trial.

Sample Size

The minimum sample size required to demonstrate non-inferiority, assuming that PaO2 levels after catheter suction in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation following cardiac surgery are 129.02±31.08 mmHg,26 with a power of 0.8, a correlation coefficient of 0.7, and estimated by PASS11, was calculated to be 49 in each cohort, or a total of 98 subjects.

Randomization

Subjects were randomized to either a control group, managed for 8 hours with CS whenever the subject showed signs of airway secretion accumulation, as per standard clinical practice for those ICUs (Table 1), or an experimental group, managed for 8 hours with automatic IL-MIE treatments (CoughSync, Ruxin Medical Systems Company Ltd, Beijing, China) performed automatically every 30 minutes, with CS performed only if signs of airway secretion accumulation manifested despite ongoing IL-MIE.

Programming was performed using SAS9.1 statistical software. Stratified block randomization was performed. Subjects were stratified by study center. After seed number and block length generation, subjects were allocated to intervention (IL-MIE) and control (CS) groups in a 1:1 ratio. Randomization was generated for at least 120 subjects by the clinical research organization managing the trial, and the corresponding randomized envelopes were provided to and kept at the two study centers. Upon enrolment into the trial, each subject was allocated one of the randomized envelopes by one of the investigators, who then opened the envelope to determine to which cohort (CS or IL-MIE) the subject had been assigned.

Blinding

Blinding was not achievable because participants and study members were able to see the presence of the investigational device.

Statistical Methods

Collected data were analyzed with a mixed model with repeated measures (MMRM), considering all observations (2 minutes before the commencement of the trial protocol and at 5 minutes, 4 hours, and 8 hours thereafter) and accounting for the baseline value of oxygenation. For the indices of oxygenation derived from blood gas measurements (PaO2, SaO2, and oxygenation index), non-inferiority was evaluated by comparison to the two-sided 95% confidence interval of the treatment effect in the MMRM model, with non-inferiority between the IL-MIE and control cohorts established if the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval for the intergroup difference in least squares mean for a measured index was found to be higher than the predetermined non-inferiority margin for that index. For the comparison of other quantitative data between groups, a two-sample t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test was used, based on the data distribution. For the between-group comparison of subjects with significant adverse events, a chi-square test was used. The number of CS treatments performed in each cohort was analyzed post-hoc as an exploratory analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® Version 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC). Statistical analysis was performed on both the full dataset collected from all 120 subjects and on the subset of 105 subjects who completed the full protocol.

Results

Participant Flow

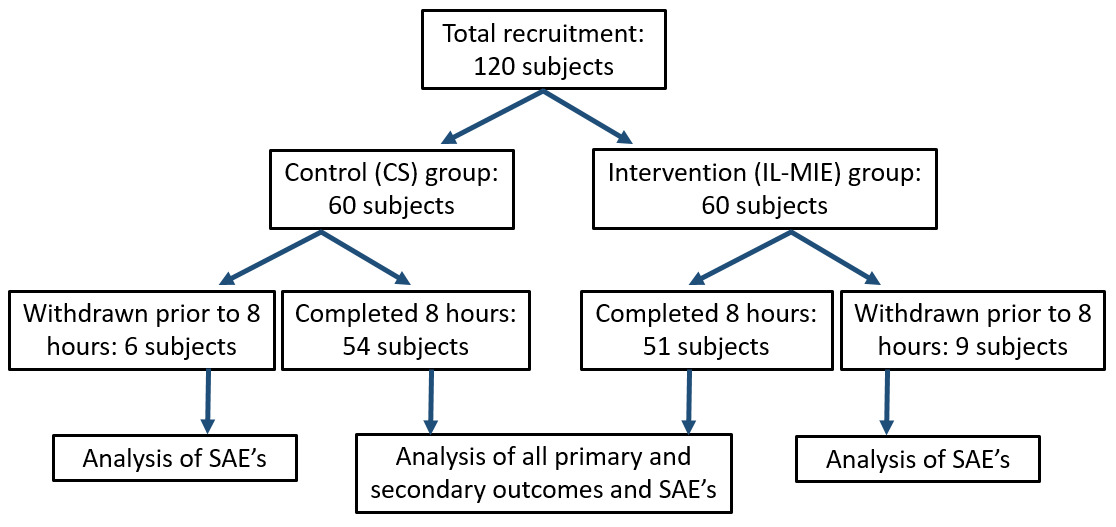

One hundred and twenty subjects were recruited into the study and randomized into control and experimental (IL-MIE) cohorts, with 60 subjects in each. Data were collected over the course of 8 hours of ventilation in 105 subjects. In 15 subjects, data collection was incomplete due to weaning from ventilation prior to 8 hours from commencement of the study, withdrawal of subject consent during the trial, or concern about the possible occurrence of serious adverse events (SAE). All 120 subjects received at least one safety evaluation, and all were included in the analysis of SAE’s. Participant flow is depicted in figure 2.

Recruitment

Subjects were recruited over a 36-month period between July 2015 and July 2018.

Baseline data numbers analyzed

The preceding surgery was either a neurosurgical (craniotomy and lobectomy) or a cardiovascular (cardiac valvar, septal, or vascular surgery) procedure. There were no significant differences between the two cohorts in terms of demographics, type of preceding surgical procedure, mode of ventilation used, ventilation parameters, vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, respiratory rate), height, or weight upon commencing the study (p>0.05 for all indices). Table 2 shows demographic and medical data for the control and IL-MIE groups at the outset of the study.

Outcomes and Estimation

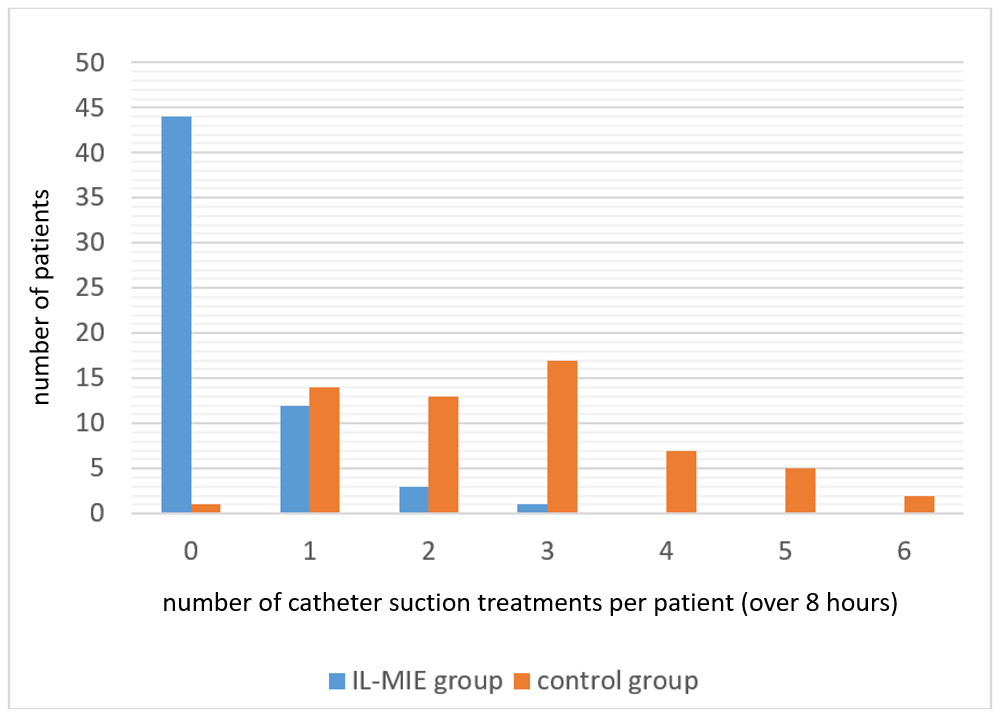

Overall, the IL-MIE group required significantly fewer CS treatments per subject than the control group (mean 0.4 vs. 2.6, p<0.001). Whereas almost every subject in the control group required CS treatments over the course of 8 hours of ventilation (59/60, 98%), most of the IL-MIE subjects (44/60, 73%) required no CS treatments at all. Those IL-MIE subjects who did receive CS (16/60, 27%) required, on average, fewer treatments per patient than the control subjects (1.3 vs 2.6, p<0.001). Figure 3 shows the number of CS treatments performed per subject in the control and IL-MIE groups.

The criteria for non-inferiority between the IL-MIE and control cohorts were met for all indices of oxygenation derived from blood gas measurements (PaO2, SaO2, and oxygenation index). Table 3 shows the intergroup difference in least squares mean (LS mean), 95% confidence interval (CI), and non-inferiority margins for these indices.

Ancillary analysis

Table 4 shows the mean values for ventilatory parameters and vital signs for the IL-MIE and control cohorts measured at 8 hours for all 120 subjects who were enrolled into the study. No statistically significant differences were found in any of the indices (P>0.05).

As a demonstrative example, Figure 4 shows the changes in mean value for the oxygenation index over time (baseline, 4 hours, and 8 hours) in this dataset.

There were no differences in mean pulse rate and blood pressure between the control and IL-MIE groups at the outset of the trial (pulse rate: 98 vs 94, blood pressure: 122/74 vs 126/75, respectively. At the 8-hour measurement, mean heart rate for the IL-MIE group was significantly lower than that for the control (90 vs. 96, p=0.047). Figure 5 shows the changes over time (baseline, 4 hours, and 8 hours) of HR in this dataset.

Approximately 860 IL-MIE treatments (each comprising 10 consecutive insufflations and exsufflations) were performed on the study group.

Harms

Two events were reported as SAEs in this group, both of which were subsequently determined to be unrelated to the use of the investigational device. In one event, a high postoperative thoracic drainage volume was noted. In the second event, chest wound healing was delayed. No other SAEs (including atelectasis, bleeding, or pulmonary edema) were reported in either group. There was no statistical difference in the incidence of SAEs between the two groups (P>0.05).

Discussion

This study showed that routine IL-MIE is safe and can minimize or completely prevent the need for catheter suction in these ventilated patients. The use of IL-MIE prevented the need for catheter suction completely in the majority of patients, and in the remainder, decreased the need for catheter suction by half. It should be noted that the control group received 100% supplemental oxygen during each catheter suction treatment, whereas the IL-MIE group did not receive such supplementation around IL-MIE treatments. Nevertheless, the IL-MIE group still demonstrated non-inferior blood oxygenation compared to the control group over the course of 8 hours of therapy. In other words, automatic IL-MIE treatments every 30 minutes resulted in less use of catheter suction and supplemental oxygen, but with an equivalent outcome in terms of the subjects’ respiratory status.

The lower heart rate found in the IL-MIE group compared to the control group after 8 hours of treatment implies a hemodynamic benefit to using a noninvasive method for secretion management as opposed to CS. This is not an unexpected finding and suggests that IL-MIE might be of particular value after neurosurgical procedures or in other situations in which elevated intracranial pressure makes preventing hemodynamic instability important.

A beneficial feature of IL-MIE is that an IL-MIE device can be configured to perform airway clearance treatments automatically, at regular time intervals continuously, even when ICU staff are not present at the patient’s bedside. This can be expected to reduce caregiver workload, particularly in patients with heavier secretion loads. The automatic nature of IL-MIE also facilitates synchronizing manual chest physiotherapy maneuvers with the IL-MIE treatments to enhance the efficacy of airway secretion mobilization.

Whereas CS typically misses the left main-stem bronchus27 and does not reach secretions beyond the first-generation bronchi, it has been reported that coughing is able to clear 7th and 8th generation medium and small bronchi28 in addition to central airways, and equally on both left and right sides.29 This implies that IL-MIE may potentially be more effective than CS at clearing secretions from the left lung and from deeper than the first-generation bronchi.

This study did not demonstrate better ventilation or oxygenation in those subjects treated with IL-MIE compared to CS. However, the design of the study made it difficult to show any possible superiority of IL-MIE over CS in this regard because the subjects of the study did not have heavy secretion loads to start with, and the trial lasted only 8 hours. As inadequate secretion clearance has been identified as an important risk factor for failed weaning from ventilation in the ICU,30–32 clarifying whether or not using regular IL-MIE improves ventilation outcome is important. Further studies are needed to assess the potential impact of IL-MIE in this regard.

A theoretical contraindication to the routine use of IL-MIE in ventilated patients is the presence of significant cardiogenic pulmonary edema, where the application of negative pressure to the airways, even for the short durations used in IL-MIE (generally less than 1 second), could enhance the movement of transudate into the alveoli. Additionally, patients who are being ventilated due to ARDS typically require high PEEP levels, which cannot be maintained during the phase of active exsufflation of each IL-MIE cough, raising concerns of alveolar de-recruitment.

However, concerning ARDS, it should be noted that CS itself disrupts PEEP, causes hemodynamic stress, and may induce deterioration in an ARDS patient’s ventilatory status. Nevertheless, CS has still been used in these patients because they require periodic secretion clearance and no viable alternative to CS (other than MIE) exists. It is therefore relevant to note that IL-MIE devices can be operated in a mode that limits the volume of exsufflated air to be no greater than the patient’s ongoing tidal volume, so as to minimize the likelihood of IL-MIE causing de-recruitment in ARDS patients.

In the context of subjects on long-term home mechanical ventilation via a tracheostomy, the potential benefits of using an IL-MIE device mentioned above will need to be balanced with the negative impact on mobility and freedom of movement that the additional bedside hardware might cause.

Possibly the greatest barrier to more widespread use of noninvasive airway-management techniques like IL-MIE in the ICU setting is the paradigm of invasive care that has historically characterized this arena. Successful integration of this technology will require overcoming that mind-set. In this regard, although nurses provide much of the frontline care for patients on invasive ventilation, a multidisciplinary interprofessional approach is needed, in which intensivists, respiratory therapists, patients, families and any other relevant stakeholders are included in the process, and appropriate protocols are developed. Recent reports from the Global Tracheostomy Collaborative and others have highlighted these principles, as well as their benefits in terms of safety, efficiency, cost-saving, and reduction of morbidity and mortality in this patient population.33–35

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the duration of the study was limited to only 8 hours, whereas the mean duration of ICU ventilation is typically longer. Second, the indication for mechanical ventilation in this study was limited to post-operative recovery only. Third, this study did not include measuring the dry weight of recovered secretions for comparison between the control and IL-MIE groups. However, considering the well-known invasive side effects of CS, the demonstration of the ability to use a non-invasive airway clearance modality to achieve the same level of oxygenation and ventilation as that achieved using CS is of significant value. The goal of secretion clearance, after all, is to facilitate optimal oxygenation and ventilation rather than to remove a specific weight of secretions. We believe that in populations for whom the use of IL-MIE is feasible, the use of the technique might fully obviate the need for CS in most patients.

In this study, heart rate was the sole indicator of hemodynamic status reported. While heart rate changes do reflect the subject’s broader hemodynamic status, the lack of more comprehensive hemodynamic data such as blood pressure or mean arterial pressure restricts the conclusions that can be drawn regarding IL-MIE’s full impact on the cardiovascular system, potentially overlooking critical hemodynamic shifts.

In addition, it should be noted that the lack of blinding between the two study cohorts may be a source of bias in this study, especially with regard to the treating nurse’s assessment of the need for CS in either cohort. For example, awareness by the treating nurse that the subject was being managed by an automated secretion clearance system (IL-MIE) may have delayed that nurse’s decision to intervene proactively with CS when signs of the need for secretion clearance first appeared. This may have resulted in fewer CS treatments in the IL-MIE cohort, unrelated to any objective patient need. While this limitation might explain, at least in part, the apparent need for significantly fewer CS treatments in the IL-MIE cohort, the authors believe that it does not diminish the importance of this finding as a potential benefit of IL-MIE. Ultimately, the value of IL-MIE in ICU secretion management will depend on its ability to minimize the use of invasive CS, regardless of the mechanism underlying that outcome, be it a physiological benefit for the patient or IL-MIE’s psychological impact on caregiver behavior, or a combination of both factors.

The limited duration (8 hours per subject) of this study precluded a meaningful analysis of the potential impact of IL-MIE on the incidence of Ventilator Associated Pneumonia (VAP) and other important complications of mechanical ventilation that typically manifest only after longer durations of ventilation.

Generalizability

This study’s generalizability is limited by its sample, involving patients undergoing mechanical ventilation during the immediate recovery period following a cardiac or neuro surgical procedure. The study did not include patients with conditions such as ARDS, or those expected to be ventilated for a longer duration. Further studies are needed to better describe the impact (if any) of IL-MIE on hemodynamic variables, and on the incidence of VAP and other longer-term complications of mechanical ventilation. In addition, future studies should aim to include a broader patient demographic so as to enhance the applicability of these findings to the broader population of ICU ventilated patients.

Conclusion

IL-MIE achieves secretion clearance in a manner that more accurately simulates normal airway clearance physiology, on an ongoing basis at frequent intervals rather than in an urgent manner prompted by sudden desaturation. Further studies will help to better understand the optimal use of this technology.

Corresponding Author

Eliezer Be’eri, MB BCh

Director, Department of Respiratory Rehabilitation

ALYN Rehabilitation Hospital, Jerusalem, 9109002, Israel

Email: ebeeri@alyn.org

Funding

The study was funded by Ruxin Medical Systems Company Ltd, Beijing, China.

Conflict of interests

Eliezer Be’eri is the named inventor on United States patent US20070017523A1 and European Union patent EU1933912 describing the technology of the device used in the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Steve Kirshblum, John Bach, Robert Brown, Joshua Benditt, Charles Sprung and Vernon Van Heerden for their assistance in the development of this technology and/or the preparation of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

The study was planned and implemented by five of the authors (JM, HD, ZJ, XM, and SZ). EB served as a clinical adviser for the staff of the participating ICUs prior to commencement of the trial. Both EB and DML were consultants in the original design of the device used in the study and assisted with preparation of this manuscript, but did not participate in the planning or implementation of the trial and were not present at the sites at which the trial was implemented.