Introduction

Problem Description

Tracheostomy care is a basic skill often shared across disciplines. However, anecdotal reports have revealed that many clinicians feel intimidated when caring for patients with a tracheostomy and may provide only minimal care to avoid creating a problem. One study concluded that healthcare providers generally lack comfort in caring for tracheostomy patients and “lack an understanding of critical tracheostomy concepts.”1 This challenge is exacerbated by the influx of new clinicians hired during the pandemic, who received little to no bedside tracheostomy experience during their training.

Available Knowledge

Pritchett and colleagues found that only 46% of registered nurses (RNs) reported being totally comfortable with changing a tracheostomy tube, and 47% were completely uncomfortable with managing accidental decannulation of a new tracheostomy. Comfort levels were only slightly higher among RNs with at least 5 years of experience and those working in intensive care unit (ICU) locations.2 These investigators also emphasized that caregiver comfort and education are critical safety considerations for patients, especially during the transition from hospital to home.2

Studies indicate that this knowledge gap extends beyond RNs. Medical students and internal medicine residents also exhibit a serious lack of knowledge regarding emergent airway care in patients with tracheostomies and laryngectomies. One study showed that 85% of them had no formal training in caring for patients with these airway devices, and senior-level medicine residents showed similar levels of knowledge as medical students regarding airway emergencies.3 Robinson and colleagues4 found that non-otolaryngology physicians scored 58% on a 10-question knowledge assessment survey, while medical students scored 64%.4 For physical medicine and rehabilitation residents, none demonstrated competence on a pre-test, achieving a mean score of 52.7%.5 Another study by Lazo and colleagues6 reported that critical care RNs scored 77.5% on a questionnaire about tracheostomy management, while medicine trainees averaged 60%, and general medical RNs scored 50%.6 Another study of 70 specialist clinicians (ear, nose, and throat (ENT) and anesthesia residents, ICU RNs, and ENT ward RNs) also demonstrated a knowledge gap in caring for tracheostomy patients with a dislodged tube.7 Speech-Language Pathologists (SLPs) also report a knowledge gap, considering tracheostomy management an area of advanced practice with infrequent exposure and limited access to specialist SLPs acting as barriers to competence and confidence in providing care.8,9

Patients with a tracheostomy may face increased risks of airway complications such as mucus plugs, accidental decannulation, and bleeding.10–12 Clinicians caring for these patients require knowledge and skills to competently and safely meet their unique needs.13 They must understand why the patient needs the airway, the importance of humidification, how to recognize respiratory distress, and when and how to suction, perform stoma care, and manage obstructed or displaced tubes.10 Davis and colleagues highlighted the significance of the knowledge gap, noting the limited literature on effective strategies to educate healthcare professionals in tracheostomy or laryngectomy care.14

An interprofessional panel of experts convened by the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation to create a consensus statement on tracheostomy care and management agreed that there are variations in care between hospitals and other care facilities. They called for efforts to standardize care to minimize complications, hospitalizations, and deaths.15

Specific Aim

The aim of this study was to determine whether there was an improvement in managing aspects of tracheostomy care after completing an online education program. The research questions were as follows:

-

Is there a difference in confidence with tracheostomy care between disciplines before training?

-

Is confidence with tracheostomy care before training related to the number of years of experience?

-

Are higher scores after training related to the number of years of experience?

-

Is discipline-specific improvement related to higher scores after training?

Methods

Context

At our acute inpatient rehabilitation hospital, we undertook a comprehensive quality improvement project regarding care of tracheostomy patients. This project included the following steps:

-

Assess the current state of tracheostomy care.

-

Assemble an interdisciplinary tracheostomy committee responsible for ensuring tracheostomy safety and quality improvement.

-

Plan for the transition to our new facility.

-

Identify the necessary bedside supplies and equipment required for the patient, as well as items that would need to accompany the patient to therapy sessions.

-

Create a documentation system enabling clinicians to easily document supplies and care practices related to the tracheostomy.

-

Develop a comprehensive training program for staff covering all aspects of tracheostomy care and the prevention of complications.

After completing steps 1-6, this study aimed to assess the effectiveness of an online tracheostomy training program for clinical staff. We aimed to provide a program for all disciplines addressing daily care and emergency management. Recognizing that each discipline has different focal points in their care, our goal was to deliver content particularly relevant to each discipline.

Interventions

Development of Educational Content

The Tracheostomy Champions group is an interdisciplinary committee tasked with quality improvement for patients with tracheostomies and laryngectomies. This committee comprises RNs, respiratory therapists (RTs), patient care technicians (PCTs), physicians, and allied health therapists, including physical therapists (PTs), SLPs, and occupational therapists (OTs). Led by the pulmonary advanced practice nurse, they initiated a quality improvement initiative beginning with revising the current policy. This was followed by creating a tracheostomy checklist to ensure the selection of a standardized location for tracheostomy supplies, presence of specific supplies, and implementation of standardized care practices for every patient. Subsequently, they created a section in the electronic medical record to ensure easy and consistent documentation of these safety measures. The final aspect of this quality improvement effort was the development of online educational modules tailored to each discipline.

The principal investigator (PI) engaged expert educators in each discipline to determine the specific content valuable to them. Objectives were formulated, and content was developed based on these objectives. Once the content was prepared, the PI collaborated with an instructional designer to create the modules. The content included PowerPoint presentations on various aspects of tracheostomy care, and embedded video clips were produced in the simulation lab. Voice-over narration was added to the PowerPoint presentations, which were then reviewed, edited, and published in Articulate Storyline,16 and evaluated by a select group of Tracheostomy Champions, consisting of 6 RNs, 2 SLPs, and 2 RTs. They were asked to review the content and indicate the time required to complete each module. This feedback proved valuable in the final editing of the modules and served as the basis for determining the amount of continuing education credit awarded for successful module completion. The nurses required the most content and were provided with a total of 3 modules, totaling 2.75 contact hours. The content of all the tracheostomy modules is detailed in Table 1.

As patient care technicians (PCTs) play a significant role in providing physical care to patients in this acute rehabilitation hospital, we deemed it was important to train them on key aspects of tracheostomy care. They were required to complete a single module lasting 20 minutes. This module covered topics such as the anatomy of a tracheostomy tube, various types of tubes, patient assessment, identification of red flags, showering protocols, tracheostomy bundle, and manual ventilation.

Documentation of Care

Another significant aspect of this project involved updating the current electronic medical record (EMR) documentation for clinicians and creating additional documentation sections. Adequate documentation of care is essential both from a liability perspective and for monitoring patient outcomes and quality. Achieving competency in a practice area, an objective of this project, must encompass adequate documentation of care delivered as defined by the providers.

Study of the Interventions

This study was conducted in a 242-bed acute urban inpatient rehabilitation hospital in the Midwestern United States. Surveys were distributed to staff before and after the implementation of a set of discipline-specific online learning modules for tracheostomy care. The discipline-specific online learning modules were launched hospital-wide in March 2019. We employed a descriptive survey design utilizing a pre-test, post-test approach and assessing self-reports of caregiver experience and confidence regarding specific aspects of tracheostomy care. The pre-test was distributed in February 2019, and the post-test was distributed in June 2019. An email containing information about the study, an online consent form, and a link to a survey created with SurveyMonkey17 was sent to participants. Participants included licensed professional staff: RNs, RTs, SLPs, OTs, and PTs. Physicians were not included in this study because they preferred their training to be conducted through live presentations rather than in an online learning format.

Procedure

This study adhered to the SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines for excellence in quality improvement studies.18

Measures

Staff were queried about their discipline and years in their respective fields. They were then asked about their experience and confidence levels regarding certain aspects of tracheostomy care, including:

-

Suctioning

-

Stoma care and cleaning

-

Tracheostomy emergencies

-

Differences in tracheostomy tubes

-

Identifying respiratory distress

-

Differences between laryngectomy and tracheostomy

-

Capping and speaking valve precautions

Categories for experience levels included one year or less (new graduate), 1-5 years, 5-10 years, 10-20 years, and more than 20 years. Questions regarding experience with tracheostomy care included a Likert scale ranging from minimal to no experience, moderate experience, much experience with this skill. Questions regarding confidence also employed a Likert scale ranging from not at all confident, moderate confidence, to very confident.

The inclusion criteria encompassed all inpatient RNs, allied health therapists, and RTs. PCTs and physicians received training but were not included in this study. Prior to the implementation of a set of online tracheostomy modules, an email was dispatched to the full distribution lists of all RNs (398), RTs (29), OTs (239), SLPs (162), and PTs (302), inviting them to participate in a survey. The same survey was repeated 3 months after the launch of the online modules and included two additional questions in the post-education survey:

-

Please provide feedback on the usefulness of the tracheostomy online module(s) in meeting your educational needs. What information did you find most important? Most helpful?

-

What additional comments do you have about this online learning program in enhancing your ability to safely care for tracheostomy or laryngectomy patients?

Two additional reminder emails were dispatched as follow-ups to increase enrollment for both the pre-test and post-test.

Analysis

We used the International Business Machines Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (Version 25.0)19 for Windows to conduct the statistical analysis. Percentages and frequencies were calculated to illustrate how participants responded to the survey questions. As participants were not matched between the pre- and post-tests, we treated them as two independent groups. When appropriate, we conducted Chi-square tests (χ2) and Fisher’s exact tests to examine if there were differences in the numbers of individuals who were confident in performing tracheostomy-related skills between those who did and did not receive the training module. All statistical tests were two-sided, and significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was granted by Northwestern University Institutional Review Board on February 13, 2019, STU00209422.

Results

Quantitative Results

In the pre-implementation survey, a total of 98 subjects responded (55 RNs, 3 RTs, 18 SLPs, 9 PTs, and 13 OTs). Among them, 11 (11.22%) were new graduates in their respective fields, 26 (26.53%) had 1-5 years of experience, 31 (31.63%) had 5-10 years of experience, 20 (20.41%) had 10-20 years of experience, and 10 (10.20%) had more than 20 years of experience.

In the post-training survey, a total of 35 subjects responded (21 RNs, 1 RT, 1 SLP, 9 PTs, and 3 OTs). Among them, 4 (11.43%) were new graduates in their respective fields, 12 (34.29%) had 1-5 years of experience, 5 (14.29%) had 5-10 years of experience, 9 (25.71%) had 10-20 years of experience, and 5 (14.29%) had more than 20 years of experience.

Difference in Confidence with Tracheostomy Care between Disciplines before Training

Table 2 shows the percentages and frequencies of participants expressing high confidence and varying degrees of confidence (from not at all to moderately confident) in providing tracheostomy-related skills within the pre-training group. Additionally, we provided the results of significant tests to examine differences in confidence among disciplines. Our findings indicate that more than half of the RNs reported feeling very confident in suctioning (70.90%) and stoma care and cleaning (58.20%). However, fewer RNs expressed confidence in managing tracheostomy emergencies (18.20%), distinguishing between tracheostomy tubes (12.70%) and between laryngectomy and tracheostomy (10.90%), identifying respiratory distress (45.50%), and implementing capping or speaking valve precautions (32.70%). Moreover, even fewer OTs, SLPs, and PTs reported confidence in performing tracheostomy-related skills within the pre-training group. In contrast, all RTs reported proficiency in most of the skills.

Relationship between Confidence in Tracheostomy Care before Training and Years of Experience

Table 3 presents the percentages and frequencies of confidence levels in providing tracheostomy-related skills among individuals with varying work experiences in the pre-training group. Individuals with more work experience (5-10 years or more than 10 years) exhibited a higher percentage reporting feeling very confident in performing tracheostomy-related skills compared to new graduates. This confidence was observed across various skills, including stoma care and cleaning (χ2= 10.2, p< .01), tracheostomy emergencies (χ2= 7.0, p< .05), differences in tracheostomy tubes (χ2= 10.6, p< .01), identifying respiratory distress (χ2= 10.8, p< .01), and implementing capping and speaking valve precautions (χ2= 6.6, p< .05). However, a considerable portion of participants with more than ten years of work experience still reported feeling not at all confident or moderately confident in providing tracheostomy-related skills (ranging from 40% to 73.3%).

Relationship between Post-Training Scores and Years of Experience

Table 4 displays the percentages of individuals who felt “very confident” in performing tracheostomy-related skills between the pre-training and post-training groups. While there was a trend of higher confidence among participants who received the training compared to those who did not, no statistical difference was observed between these two groups across various skills, including patient suctioning, stoma care and cleaning, tracheostomy emergencies, differences in tracheostomy tubes, identifying respiratory distress, differences between laryngectomy and tracheostomy, and capping and speaking valve precautions. More than half of the participants reported feeling “very confident” in patient suctioning (55.9%) and identifying respiratory distress (51.40%). However, less than one-fifth of the participants felt very confident in managing tracheostomy emergencies (17.60%) and identifying the difference between laryngectomy and tracheostomy (20%).

Relationship between Discipline-Specific Improvement and Post-Training Scores

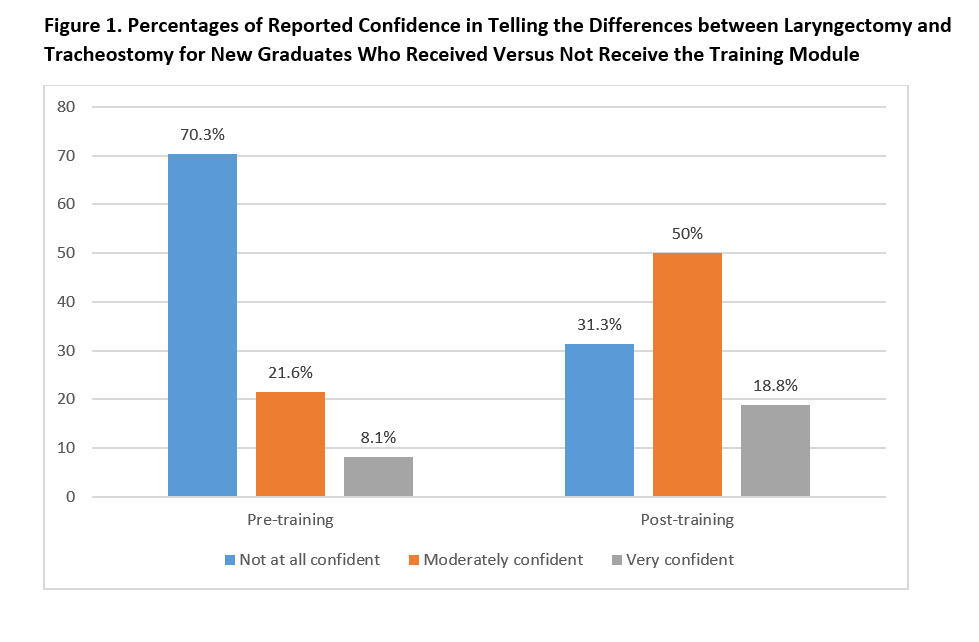

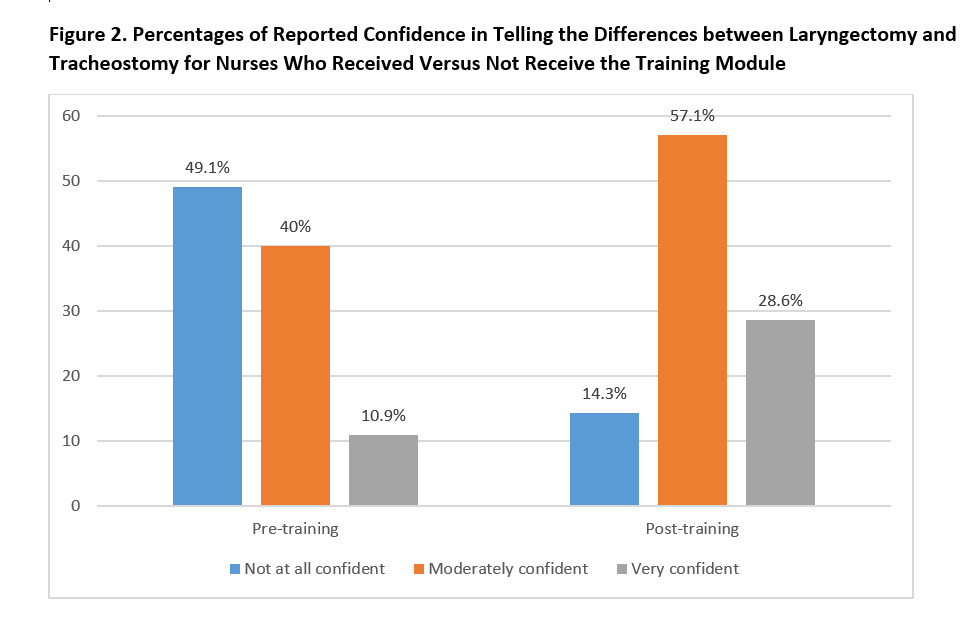

New graduates who completed the training module exhibited significantly higher confidence in distinguishing between laryngectomy and tracheostomy compared to new graduates who did not receive the training module (Figure 1) (χ2 = 7.07, p = .025). Specifically, among RNs, a greater number of participants who completed the training module expressed high confidence in distinguishing between laryngectomy and tracheostomy compared to those who did not complete the training (Figure 2) (χ2 = 8.97, p = .008).

For other professionals, there was no significant difference observed between those who completed the training and those who did not. Additionally, among clinicians with more work experience, there was also no significant difference between those who completed the training modules and those who did not.

Qualitative Results

The two open-ended questions at the end of the post-test provided some narrative data about the helpfulness of the modules. Comments included:

“The modules and resources provided were incredibly helpful–cannot thank you enough for creating these for everyone. I feel much more confident and knowledgeable about trachs/airways and management of them. I also feel like I would know when to question certain things, proper questions to ask the physicians, and will have much improved assessment skills. I wish this could be done on all body systems/diagnoses we see on the unit!”

“The information about trach emergencies was very helpful as I lack experience in these.”

“I appreciated the videos, the walk step by step walk-throughs, and the detailed information.”

“Review of the different kinds of tubes was helpful. Also, review of emergencies is always good since these occur less frequently.”

When asked about their ability to safely care for the tracheostomy or laryngectomy patient, comments included:

“I am better equipped to address tracheostomy emergencies than I was prior to the online learning program. However, I am a very hands-on learner and would find an optional skills checkout helpful for those staff members that would like to troubleshoot tracheostomy emergencies and use the models for practice their suctioning technique.”

“I thought the online modules were somewhat helpful, but I was expecting more during the actual in person class. I didn’t feel like it really added to my knowledge base too much and I think it would be helpful to have some hands-on practice skills incorporated somehow.”

Discussion

Results of the pre-survey demonstrate that gaps in knowledge and limited comfort with tracheostomy skill performance are common among healthcare professionals in our surveyed group. There is a clear need for focused training in this subject area. Similar educational interventions have resulted in improvement in clinicians’ self-reported comfort or confidence in caring for patients with tracheostomies, as well as improvements in objective knowledge related to tracheostomy management. One such study of 94 healthcare professionals using a standardized tracheostomy education model showed improvement in the providers’ objective knowledge as well as subjective comfort managing tracheostomies.20

Several studies have demonstrated the positive results of tracheostomy training programs. Roof and colleagues showed improvement in scores from 36% to 69% after a one-hour live workshop.21 In our study, while there was a trend of higher perceived confidence overall for participants who received the training compared with those who did not, these differences were not statistically significant for the most part. The education modules resulted in statistically significant improvement in confidence identifying laryngectomies vs tracheostomies in the RN group and the new graduate group. These results suggest that virtual didactic training alone may not be sufficient to achieve meaningfully increased confidence in tracheostomy skill performance and management of tracheostomy emergencies.

Simulation or other novel methods of interactive training, in combination with didactic content, may have produced greater benefit. One group used a short PowerPoint presentation followed by the use of a doll to run through standardized algorithms for managing tracheostomy emergencies. After training, all 60 staff reported feeling confident or very confident during a tracheostomy emergency.22

A small study of 35 RNs in a surgical acute care setting examined confidence levels in managing tracheostomy emergencies and performing tracheal suctioning, as well as other tracheostomy care skills. That study utilized hands-on scenarios run in a simulation lab. Pre- to post-intervention, RN confidence increased across all measured values.23 Another study providing a similar combination of didactic and hands-on simulation-based education showed statistically significant increases in both perceived confidence and objective knowledge post-intervention for a group of 85 resident physicians and advanced practice providers. Many, though not all, of these gains were retained at 6 months post-intervention.9 A study using a combination of didactic and simulation-based education intervention for pediatric healthcare professionals had similar success, with improvements seen in objective knowledge, subjective comfort, and actual skill performance post-intervention.19

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, medical facilities and universities have increasingly relied on virtual training and education for staff. Virtual training has the advantage of flexibility. It may be completed by the staff member at any time of day, does not require pulling staff out of their duty assignment, and eliminates the need for a physical teaching space. One study found that webinar education on tracheostomies provided significant improvements in communication, clinical assessments, and clinical governance, with a positive impact on decannulation and quality improvement. They promoted the feasibility of virtual learning to disseminate best practice but also suggested hands-on experience for technical mastery.24

The benefits of in-person hands-on training should not be minimized. The available evidence suggests that even a short amount of time spent on hands-on learning can have an appreciable impact on healthcare providers’ perceived confidence and actual skill performance when it comes to caring for patients with tracheostomies. Several of the studies discussed here dedicated relatively short amounts of time to simulation training, some as little as 30-60 minutes.25

It is also worth noting that not all schools and hospitals have access to high-fidelity simulation manikins for training purposes. The literature includes other alternative methods of education apart from traditional didactic methods and high-fidelity simulation. One university successfully developed a “tracheostomy overlay system,” a vest worn by a standardized patient actor that allows for the performance of tracheostomy care skills with feedback about skill performance coming from embedded sensors.25 Another program used a game-based virtual reality app that learners could access from their smartphones. Learners who used the app performed better when observed completing tracheal suctioning and peristomal skin care, compared to learners in the control group.26

Limitations

One limitation of this study is the low response rate and the single study site. Of the possible 830 professionals, only 98 completed the pre-implementation survey, and a mere 35 completed the post-implementation survey, despite repeated attempts to increase recruitment. This resulted in a final response rate of 8.78% for the initial survey and 3.1% for the post-survey. Another limitation is the inability to ensure a true pre-test, post-test methodology due to the significantly lower number completing the post-test. Ideally, if we could match participants with pre- and post-tests, we might gain insights into the true intra-participant change after training. The lack of this link limits our ability to draw robust conclusions. Furthermore, we did not assess long-term learning, which is another limitation. If we had conducted a follow-up assessment at 6 months and/or 12 months, we might have gained insight into the retention of learning or validated the need for retraining at intervals. A final limitation is the exclusion of physicians from this study. Although their training was conducted through live lectures and discussion sessions, they were still integral members of the interdisciplinary team. After the conclusion of this study, they did receive subsequent online training tailored to their role.

Conclusion

Training methods for critical content (high risk, low exposure) may require not only repeated training but also more than one primary teaching method to achieve mastery. Managing patients with tracheostomies includes knowledge of routine care as well as critical thinking skills when seconds count. Providing didactic content with online learning modules achieves consistency in delivering the message, offers opportunities for review at convenient times for the learner, and allows for re-review as needed. However, to effectively master critical content, other methods such as simulations, hands-on skills practice, and bedside rounds can be beneficial for synthesizing material.

Corresponding Author

Linda L. Morris, 8305 A Highpoint Circle, Darien, IL 60561, Email: lmorris02@sralab.org; lmorris@LindaMorrisPhD.com, 630-212-3553

Institution

Shirley Ryan AbilityLab (formerly the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago)

Author Contributions

All authors had full access to the data in the study. CRediT Roles: Conceptualization: LLM, Data curation: LLM; Formal analysis: JW, LLM SPM, AS-S, KE, AB; Funding acquisition: none; Investigation: LLM; Methodology: LLM; Project administration: LLM; Resources: LLM; Software: JW; Supervision: LLM; Validation: LLM, JW; Visualization: LLM, JW; Writing-original draft: LLM, SPM, AS-S, KE, AB, JW; Writing-Review & editing: LLM, SPM, AS-S, KE, AB, JW.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Morris discloses royalties from her book, Tracheostomies: The Complete Guide, 2nd ed., (Morris & Afifi, eds., 2021, Wilmette, IL: Benchmark Health Publishing). She also declares income from her role as president of Dr. Linda L. Morris, Inc., doing medical-legal consulting as an expert witness, some of which involves tracheostomy cases. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial Support

none