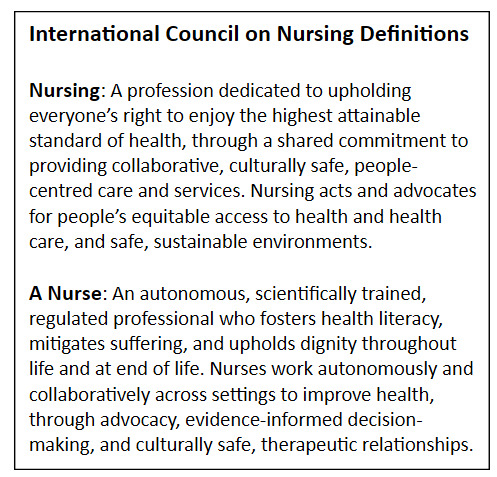

Tracheostomy care sits at the intersection of advanced practice, health systems, and human experience, demanding collaboration, communication, and advocacy across disciplines. The International Council of Nurses’ (ICN) 2025 redefinition of nursing and nurses provides a global framework that helps tracheostomy teams advance health and dignity together.1 The updated definitions (Figure 1) highlight nursing’s scientific foundations alongside its ethical commitments to equity, health literacy, and cultural awareness. This vision aligns with the Global Tracheostomy Collaborative’s (GTC) mission and provides a shared language that unites professionals, patients, and caregivers in the pursuit of safe, inclusive care.

New Definitions for Nursing and Nurse: Creating Partnership Across Health Professions

The new ICN definitions for Nursing and Nurse support teamwork across disciplines and emerged from more than a year of global consultation, literature review, and expert consensus.1 The definitions incorporate perspectives not only from national nursing associations but from regulators, educators, policymakers, and patient advocates.1 These definitions have implications for the professional identity for nurses and for partnerships that span health disciplines, given the engagement of nurses across a wide range of healthcare-related efforts. In tracheostomy care, team-based practice is critical, so clarifying the scope and essence of nursing supports partnership, reframing how nursing is understood, practiced, and positioned within health systems worldwide.

Far more than linguistic updates, the new definitions establish a values-driven foundation that connects nursing practice to broader global priorities in healthcare. In tracheostomy care, there is alignment between GTC goals for improving care standards and ICN priorities such as Universal Health Coverage (UHC), Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and commitments to planetary health and cultural responsiveness. Nursing refers to the profession, grounded in disciplinary knowledge and ethical principles, and a nurse is the individual practitioner licensed to deliver care. These complementary concepts encompass collective responsibility and individual accountability that integrate into interprofessional models of care, including those advanced by the GTC.

Tracheostomy Care as a Shared Journey

The new definitions align with GTC’s mission to improve the quality, safety, and experience of care for all people with tracheostomies.2 Efforts are pursued through interprofessional teamwork, patient and family engagement, data-driven quality improvement, and the equitable dissemination of best practices.3 In GTC-affiliated institutions, nurses partner with speech language pathologists, respiratory therapists, and physicians to operationalize evidence-based protocols, maintain continuity across care settings, and advocate for culturally competent, person-centered care. These contributions reduce adverse events, minimize unnecessary delays in communication and decannulation, and optimizing long-term outcomes.4–8

The ICN’s call for “people-centred, culturally safe, and ethically grounded care” is central to tracheostomy safety and recovery. Patients often face isolation, loss of voice, stigma, and inequities tied to race, language, or disability. Nurses play a critical role in addressing these challenges through frontline care, teaching and education, family engagement, advocacy, and research ass illustrated in Figure 2. The ICN’s emphasis on collaboration across care settings mirrors the GTC’s interprofessional model, reminding us that tracheostomy care extends beyond decannulation or discharge and must integrate the lived experiences of patients and families.9,10 Together, the ICN vision and GTC approach highlight nursing as a strategic partner in advancing safe, equitable tracheostomy care.

Achieving Continuity from Hospital to Home

Tracheostomy care unfolds across a continuum from the ICU and hospital wards to rehabilitation facilities, homes, and communities. At each stage, nurses provide coordination, vigilance, education, and emotional support, reflecting the ICN’s definition of the nurse as an autonomous, scientifically trained professional who fosters health literacy, alleviates suffering, and upholds dignity. In acute and transitional care, they safeguard the airway, manage complications, and prepare families for home management. Research shows that nurse-led protocols reduce dislodgement, infection, and obstruction, while discharge planning and caregiver training are especially critical for children, medically complex patients, and those from marginalized backgrounds.4,11–14

Beyond the hospital, nursing presence continues in the community through home visits, school health programs, and telehealth support. These roles build caregiver confidence, prevent unnecessary hospitalizations, and foster what the ICN calls “culturally safe, therapeutic relationships” grounded in respect and shared decision-making.15 Together, the ICN’s global vision and the lived practice of nurses across the tracheostomy journey affirm that while surgery and technology provide life support, it is continuity of care and advocacy that transform it into safe, connected, and dignified living.

Examples of these principles are depicted in cases of tracheostomy care restoring voice (Figure 3) and Supporting families through transition (Figure 4) These cases illustrate the relational depth, anticipatory thinking, and cultural empathy that define nursing beyond tasks or procedures.15,16 They also highlight how nurses often provide continuity across ICU, ward, and community care. For patients and families, it is these consistent, compassionate interactions that often shape their perception of safety and trust in the system. As GTC continues to promote evidence-based models, such narratives remind us that data and outcomes are grounded in human experience, with nurses often at the heart of those stories.

Interprofessional Collaboration and Accountability

Tracheostomy care is inherently interdisciplinary, requiring coordinated efforts from physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, speech-language pathologists, dietitians, social workers, and critically patients and families. The updated ICN definitions affirm nursing as both autonomous and collaborative, with responsibility for evidence-informed practice and therapeutic relationships. This framing echoes the GTC experience: safety improves when roles are clear, expertise is respected, and accountability is shared. Many of lessons from the pandemic area relating to centering patients and collaborative care have proven enduring principles in an evolving care landscape.17–22

Nurses often serve as system integrators, bridging professions across the continuum of care. Their constant presence at the bedside and in transitions positions them as central communicators and leaders—whether coordinating huddles, mobilization protocols, or airway emergency responses. In successful GTC sites, such leadership reduces silos, delays, and miscommunication while building trust across teams. The ICN’s redefinition is thus a call to co-create systems that advance safe, equitable tracheostomy care. When all team members are equal partners in rounds, planning, and policy development, the quality of decisions improves and patient outcomes and satisfaction rise.2

Empowering Families and Enhancing Health Literacy

One of the most profound elements of the updated ICN definitions is the explicit acknowledgment of the nurse’s role in enhancing health literacy and fostering dignity across the life span.1 Nowhere is this more critical than in tracheostomy care, where patients and families must rapidly acquire life-sustaining knowledge and confidence. Nurses guide families through suctioning, humidification, stoma care, emergency preparedness, and use of speaking valves or ventilators, tasks taught, repeated, and clarified not only for technical success but to build resilience. Families must also navigate home nursing agencies, insurance barriers, school systems, and social stigma, making health literacy less about reading comprehension than about acting on information in culturally and emotionally safe ways.

The ICN recognizes that nurses do not simply impart knowledge, they co-create understanding. This requires adapting to cultural contexts, language preferences, and emotional needs. In GTC centers, this has included multilingual resources, simulation-based training, and caregiver forums that exemplify person-centred, culturally safe care. When families are empowered, outcomes improve: confident caregivers reduce emergency visits, enable earlier decannulation, and enhance quality of life.3 In many cases, it is the nurse who bridges clinical instruction and lived experience, who sees, listens, and adapts. As one caregiver reflected, “The nurse didn’t just teach me how to suction. She taught me how to breathe again.”

Leadership, Innovation, and Global Equity in Tracheostomy Care

The ICN’s 2025 definitions invite us to see nurses not only as clinicians but also as leaders, innovators, and agents of equity, an especially urgent vision in global tracheostomy care, where disparities in access, training, and outcomes persist.1 In resource-limited settings, nurses are often the most consistent and adaptable providers, managing clinical care while advancing education, advocacy, and systems navigation. From initiating decannulation protocols in rural hospitals to training caregivers in remote villages, they deliver localized, sustainable innovations that reduce harm and restore voice.2

The ICN affirms that nurses are accountable for system design, service transformation, education, and leadership, roles already evident in the Global Tracheostomy Collaborative (GTC).1 Nurse-led projects have accelerated speaking valve use, shortened time to oral intake, and improved caregiver readiness for discharge.3 Beyond quality improvement, nurses are increasingly shaping research on safety, communication access, and family experience, ensuring that innovation is both evidence-based and grounded in patient priorities. True equity in tracheostomy care requires solutions tailored to resources, cultures, and community needs, and nurses are uniquely positioned to bridge these dimensions, translating global ideals into local impact.

Practical Implications Across Stakeholders

The ICN’s updated definitions provide practical direction for improving tracheostomy care across hospitals, rehabilitation facilities, and home settings, as well as across socioeconomic and geographic boundaries (Figure 5). By emphasizing equity, dignity, and shared responsibility, these definitions can guide policy, strengthen education, and foster respect across disciplines. Their adoption creates a common language that helps align diverse stakeholders, clinicians, administrators, patients, and families, around a unified vision of safer, more inclusive care.

Care pathways and governance structures must be built to honor the expertise of every team member, from nurse and respiratory therapists to speech-language pathologists, physicians, dietitians, social workers, and family caregivers. Families, who carry the daily responsibility of suctioning, communication support, and emergency readiness, are indispensable in care. When interprofessional integration is supported through shared decision-making, simulation training, and quality improvement projects, outcomes improve and transitions become smoother.12 Anchoring tracheostomy care in the ICN framework reinforces that safety, recovery, and dignity are collective responsibilities, achieved when all voices are heard and all contributions are valued.

Conclusion

The 2025 ICN definitions provide a shared language that links safety, equity, and dignity across settings. They affirm the unifying role of nursing and how optimal outcomes depend on coordinated efforts among all team members, patients, and families, guided by trust, continuity, and cultural understanding. By adopting this vision, the tracheostomy community can strengthen collaboration and deliver safe, compassionate, high-quality care.

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures

None

Funding

Center for Immersive Learning and Digital Innovation: A Patient Safety Learning Lab advancing patient safety through design, systems engineering, and health services research, Vinciya Pandian (R18HS029124)