Background

A tracheostomy is a surgically created artificial airway via an external opening into the trachea that allows the individual to breathe.1 Clinical indications include: 1) bypassing an obstruction in the upper airway, 2) maintaining a patent airway in the presence of severe injury or upper airway procedures, 3) protecting airway in the presence of absent airway protective responses, and 4) assisting with long-term ventilation.2 Patients who are successfully weaned from a tracheostomy tube have shown improved rehabilitation and survival rates, increased possibility of home care management, and have a positive financial impact on the healthcare system by reducing costs.3,4 In addition, caring for a patient with a tracheostomy tube on an inpatient hospital unit results in a greater workload for the nursing staff as extra assessment and interventions are required in this patient population. Therefore, decannulation should be the goal unless the tracheostomy tube was inserted for an irreversible condition.5 Decannulation is defined as the removal of the tracheostomy tube from the patient’s trachea allowing the patient to breathe normally via their upper airways. It is important to note that the terms “corking” and “capping” are used interchangeably in the literature and in our institution. For consistency, this paper will use the term “capping” throughout as this is the more accepted term.

Historically, patients with tracheostomy tubes were cared for by nurses in critical care, but over the last decade these patients are now also cared for on general medical and surgical units.6 The role of the nurse is to provide patient assessment and support to be able to optimize return to normal body functioning, improved sense of well-being and quality of life.6 The latter is usually done in collaboration with the multidisciplinary health care team, including advanced practice nurses [APN], who play a leading role in the development of clinical practice guidelines and protocols, promote evidence-based practice and provide support and expert consultation.7 Nurses play a key role in the decannulation phase of the patient’s tracheostomy trajectory by providing the daily monitoring and use their critical judgement to assess the patient’s tolerance of the capping trial.

The literature demonstrates specific criteria to consider prior to initiating a capping trial. The following list of criteria suggest a patient’s readiness for decannulation: 1) upper airway patency, 2) adequate level of consciousness, 3) adequate respirations, 4) effective secretion management, 5) type and size of tracheostomy tube (cuffless and a size less than 6mm), 6) adequate airflow around the tracheostomy tube, and 7) effective cough.4,5,8–14 Once these criteria are assessed as being met, the patient becomes eligible to undergo a capping trial. A capping trial occurs when a cap is placed over the tracheostomy tube to block the artificial airway so that when the patient inhales/exhales, air will bypass the tracheostomy tube and will pass via the patient’s mouth and/or nose. A capping trial is done prior to decannulation to determine whether the patient can function without the tracheostomy prior to it being removed. For example, clinicians assess whether the patient can manage their own secretions and either swallow them or expectorate them via their upper airway and mouth. Patients who are capped without assessing their readiness or are capped and not placed on an appropriately structured trial with monitoring may have their tubes removed prematurely and experience adverse events (e.g., upper airway obstruction), which are a potential cause of neurological morbidity and death.4 There are also delays in decannulation, whereby the patient is left with a tracheostomy tube for longer than is clinically required. Therefore, a structured approach to initiating a capping trial is imperative.

Published literature reviews9,15 showed no clear systematic process or technique for conducting a capping trial or process of weaning. Most of the included studies consisted of literature reviews or expert opinion of low to moderate quality, with little consensus or evidence about the process of weaning. Different methods were described, including finger occlusion, use of a cap or a one-way speaking valve to occlude the tracheostomy tube, downsizing the tracheostomy tube, or the use of a tracheostomy plug or retainer. The review concluded there was a lack of clinical studies on the weaning techniques, which may be related to the inability to blind patients and investigators, the inability to predict the anatomical or physiological status of the patient prior to decannulation, and multidisciplinary involvement in tracheostomy decannulation procedures.

At the McGill University Health Centre [MUHC], for the adult patient population, a protocol was developed in 2016 to: 1) standardize care provided to adult patients with tracheostomies, 2) to harmonize practice and ensure that proper capping techniques were being utilized, and 3) to prevent complications associated with the apparatus. Recommendations from a team of clinical experts and evidence-based literature were the foundation for outlining the required criteria to initiate a capping trial, the method and time schedule, and the monitoring required during the trial. In addition, two modifications were also introduced to accommodate patient circumstances resulting in a 24-hour capping trial and a gradual capping trial. However, this process was never formally evaluated. It is important to note that a “capping trial” in this article refers to the 100% occlusion of the diameter of the tracheostomy tube.

In summary, given the existing knowledge gap in the literature regarding capping trial processes, the lack of a formal evaluation of the MUHC protocol, and various insights gained from firsthand experience in caring for this patient population, it was crucial to assess whether the MUHC’s capping trial protocol reached the goal of providing a structured method of a capping trial to ensure that patients can be successfully decannulated in a timely fashion.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to assess whether patients with a tracheostomy tube could be successfully decannulated following the MUHC capping trial, by evaluating the proportion of patients successfully decannulated and whether several clinical indicators had an impact on the outcome.

Our specific research questions were the following:

-

Do patients who are placed on the MUHC capping trial protocol achieve successful decannulated in the set timeframe determined by the tracheostomy team?

-

Is there a significant difference between the groups (those who pass the capping trial and those who fail) in relation to characteristics of age, anxiety level and/or level of alertness?

Methods

Study design

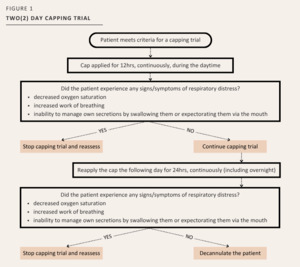

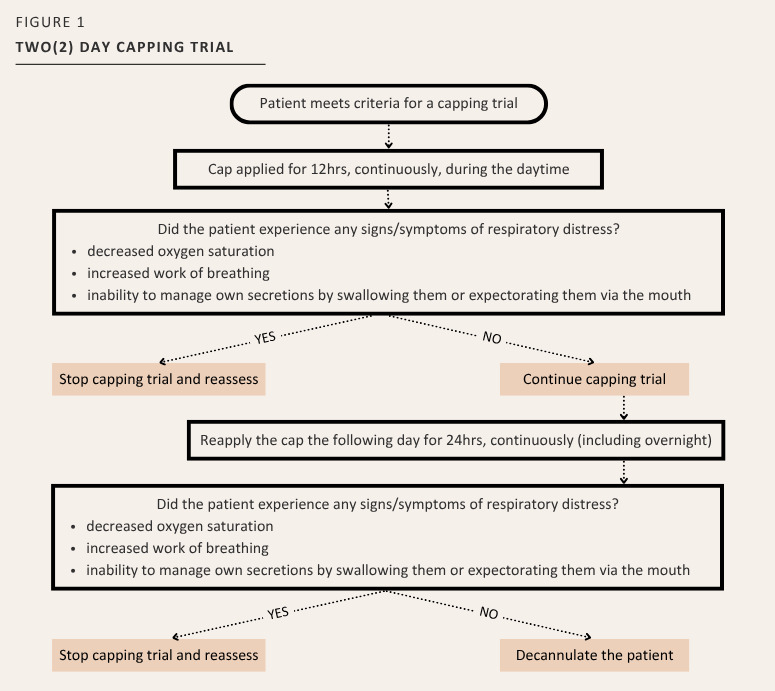

A descriptive observational study design was used, whereby all inpatients with a tracheostomy tube were assessed and followed by the tracheostomy team that consisted of an Otolaryngologist [OTL] – Head and Neck Surgeon, Respiratory Therapist [RT], APN, and Speech Language Pathologist [SLP]. The patient’s medical plan and progression in the tracheostomy trajectory were discussed. Patients were then identified for possible decannulation based on established criteria as per the protocol. Once identified, patients were placed on a capping trial using a set of pre-printed orders [PPO] describing the capping trial schedule to be followed. The tracheostomy capping trial included a 12-hour, daytime period of capping on Day 1, and a 24-hour period of capping (day and night) on Day 2 (See Figure 1). Consensus was obtained by the tracheostomy team to determine that the patient was eligible for a capping trial. If the patient could not provide consent, a surrogate decision maker was sought. A sample size of 128 patients was the aim to examine mean difference using t-test for continuous variables with an alpha of 0.05, power of 0.80 and medium effect size.16

Instruments

Once the tracheostomy team had assessed that the patient had met all the eligibility criteria to start a capping trial, a six-item short-form of the State Anxiety scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-6)17 was completed with patients who had cognitive capacity. If the patient lacked the capacity, the STAI-6 questionnaire was not completed but they could still remain in the trial. The STAI-6 is a frequently used and validated tool to measure anxiety. It has been used to determine levels of anxiety in patients prior to surgery and/or undergoing a procedure.17–19 This self-report questionnaire has 6 items, allowing the patient to rate their feelings of calm, tense, upset, relaxed, content, or worried based on a scale from: not at all (1), somewhat (2), moderately (3), and very much (4). Specific items are reverse coded so that higher scores indicate a higher level of anxiety.17 Once this was completed, the patient was placed on the MUHC tracheostomy capping trial within 24 hours and the subsequent monitoring and evaluation took place according to our protocol.

An in-house data extraction tool was created to collect information from the patient’s medical record. Variables recorded include diagnosis, past medical history, age (years), sex, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score at the time of the initiation of the capping trial, in addition to the questions detailed below:

-

Did the cap remain on the patient’s tracheostomy tube for the prescribed timeframe?

-

Did the patient experience any signs or symptoms of respiratory distress while on the capping trial?

Ethics

The tracheostomy capping trial study (REB Project # 2020-5456) received Research Ethics Board approval and authorized to conduct human subjects’ research from the McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Québec, Canada on August 25, 2021. All procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines.

Setting

The MUHC is a bilingual academic multisite quaternary healthcare network in Montreal, Québec, providing specialized medical services for complex and high-acuity cases. This study was conducted at a single adult hospital site and excluded only patients admitted to respiratory intensive care unit as this patient population is not included in the MUHC tracheostomy team’s mandate. This does not exclude other patients with respiratory diagnoses who are admitted to another unit.

Participants

All patients, 18 years of age or older, with a tracheostomy tube, regardless of location on the hospital site (except the respiratory intensive care unit), whose readiness for decannulation had been assessed by the tracheostomy team and who have met the following criteria were started on a capping trial.5,8–13

-

English and/or French speaking.

-

Alert and competent to provide consent. In the event the patient lacked capacity, consent was sought from the person authorized to provide consent on their behalf as per the Civil Code of Québec. In the event a surrogate decision maker was unavailable or refused to provide consent, the patient was not enrolled.

-

A patent upper airway with no upper airway anomalies, assessed via one of the following:

a. A fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), which would allow for visualization of the upper airway.

b. Whether the patient tolerated a one-way speaking valve.

c. A portable scope to visualize the upper airway, if the patient had not had a FEES or has tolerated/used a one-way speaking valve.

-

Appropriate level of consciousness: GCS >8.

-

Respiration rate: breaths 12-20 breaths per minute or within the patient’s baseline, and had an oxygen saturation ≥ 90% with an FiO2 ≤ 40%.

-

Adequate secretion management defined as tracheal suctioning no more than 4 times in a 24-hour period, and able to expectorate secretions via their mouth or swallow them when wearing a one-way speaking valve, (a limit of 4 suctioning episodes within a 24-hour period was established, as some patients expressed a preference to be suctioned even in the absence of clinical necessity. Additionally, certain nurses routinely performed suctioning or did not consistently encourage patients to expectorate secretions independently. As a result, suctioning of less than 4 times could not be reliably interpreted as an indicator of a patient’s readiness for decannulation.)

-

Ensuring the tracheostomy tube was less than or equal to 6mm, and was cuffless.

-

Assessing for possible phonation: ensuring sufficient airflow around the tracheostomy tube by assessing the patient’s tolerance of finger-occlusion and/or the use of a one-way speaking valve.

-

Assessing coughing ability and force: patient’s ability to cough, to mobilize their own secretions.

For this study, patients with a tracheostomy tube were excluded from this specific capping trial schedule if they met any of the following criteria:

-

Had not met all the eligibility criteria to start a capping trial as mentioned above.

-

Had known or suspected obstructive sleep apnea [OSA] as assessed by the OTL physician.

-

Admitted with a tracheostomy tube on the respiratory intensive care unit.

-

Patient could not be placed on a capping trial over the weekend due to the decrease in nursing and physician staff.

Data collection

Data was collected via chart review when the capping trial was taking place as well as post-decannulation. In addition, discussions were held with the unit nurse on patient tolerance of the capping trial. Our in-house data extraction tool was used to record the findings. Finally, patients were considered to have “successfully passed” (were decannulated) the MUHC capping trial if all the following 3 identified outcomes were achieved. If not, the patient had any sign or symptoms of respiratory distress or if they were not able to manage their own secretions, they would be considered to have failed the capping trial. This data was also collected on an in-house data extraction tool whereby answering the following questions in a “yes” or “no” format, in addition to keep track of their capping timeline:

-

The patient showed no signs or symptoms of respiratory distress (Yes/No). If experiencing respiratory distress, that would lead to a termination of the capping trial;

-

The patient was able to manage their own secretions without the need of any suctioning via the tracheostomy tube as shown by the patient’s ability to either expectorate secretions via their mouth, suction secretions via their mouth, and or swallow secretions (Yes/No). If unable to manage their own secretions, that would lead to a termination of the capping trial; and

-

The patient’s tracheostomy tube was removed with no signs or symptoms of respiratory distress post-decannulation procedure (Yes/No).

Capping Trial Procedure

The procedure can be described as the actual capping process whereby a universal clear cap is placed on the opening of the inner cannula to block any air-entry via the tracheostomy tube.

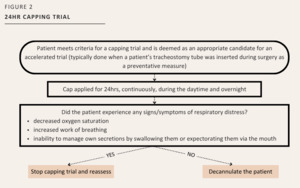

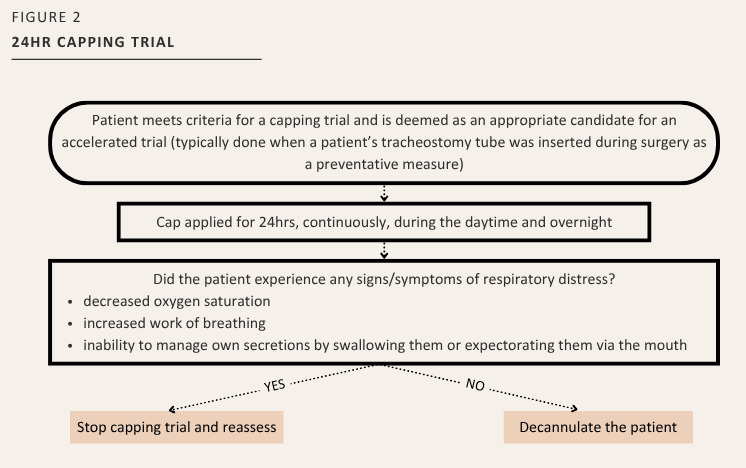

Of note, the physician in charge of the tracheostomy management could make the following modifications:

-

Accelerate a patient’s capping trial to only a 24-hour period, when appropriate (See Figure 2). This was determined by the assessment of the tracheostomy team to identify if criteria above for decannulation readiness was achieved, or

-

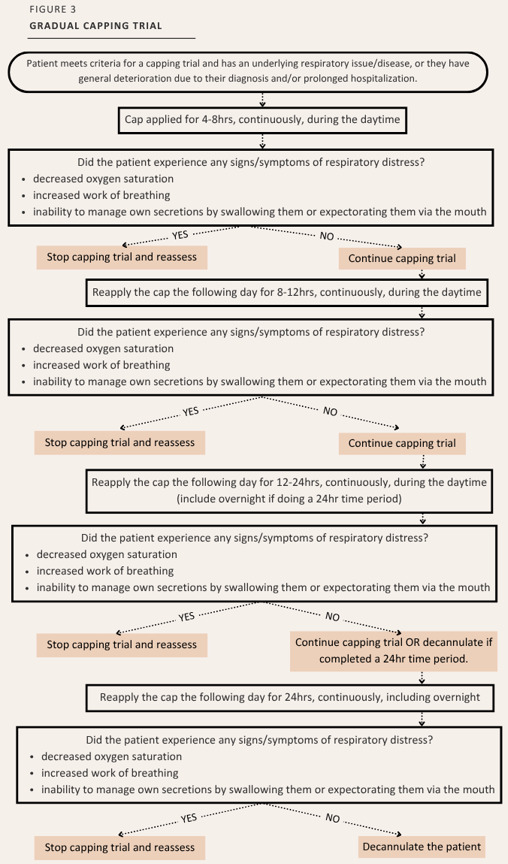

If the patient’s condition warranted, place the patient on a “gradual capping trial” to extend the trial. A “gradual capping trial” would last longer than 2 days and was applied either because of an underlying respiratory issue/disease, general deterioration due to the diagnosis and/or prolonged hospitalization or had previously demonstrated general signs and symptoms or respiratory issues or difficulty managing their own secretions. (Figure 3).

When it is determined that the patient has in fact passed the trial, they would be decannulated at the bedside by the OTL resident or a respiratory therapist from the tracheostomy team. After decannulation, the tracheostoma was cleaned with normal saline and an occlusive dressing was applied. Teaching was also provided to ensure that the patient applied pressure to the tracheostoma site when speaking, coughing, or sneezing to promote tracheostoma closure.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using an Excel Spreadsheet and the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, IBM 25) software program. Patient demographic, medical and tracheostomy status baseline information was compiled and analyzed to describe sample characteristics. The tracheostomy capping assessment and procedures were extracted from the patient’s electronic chart. Depending upon the type of variable, nominal data were analyzed to obtain a frequency count and %, whereas continuous variables (age, STAI, GCS) were analyzed for mean and standard deviation (SD), or other non-parametric test such as chi-square or t-test or one-way ANOVA to be performed to examine relationship between groups, if appropriate.20 Significance level was set at p-value of less than 0.05.

Terms

Note the definitions of terms in Table 1.

Results

A total of 44 patients participated in the study (Table 2). The mean age was 61.1 years (SD=13.15), with the majority of participants male (75%). The most common reasons for the tracheostomy tube were due to either OTL surgery (39%) or for a prolonged intubation in the intensive care unit (48%).

Of the 44 patients in this study, 39 (89%) were successfully decannulated. Of the 39 patients successfully decannulated:

-

34 (87%) required one capping trial attempt

-

2 patients self-decannulated

-

3 patients passed the trial on the Friday but were decannulated after the weekend. This is due to an institutional policy whereby decannulation takes place only when an OTL physician is on site. These patients were not decannulated on the Friday and there were no OTL physicians on site during the weekend.

Of the 5 patients that were not decannulated, 1 patient died during the study due to an unrelated cause. Table 3 shows the characteristics of the 4 patients who failed their capping trial.

From the 44 patients, a total of 54 individual prescribed capping timeframes were conducted (Table 4). Six patients (13.6%) underwent more than 1 trial attempt. From the 54 individual prescribed capping timeframes, 39 were initiated using the two-day capping trial, step 1 (12-hour daytime capping), while 15 deviated from the standardized protocol. There were 35 trials that progressed to Step 2 for the 24-hour timeframe, while 6 deviated from the protocol and required a Step 3 (n = 4) and a Step 4 (n = 1).

Age and Decannulation Success

The mean age of the individuals who were successfully decannulated was 61.5 years (SD=13.15). The mean age of the individuals who were not successfully decannulated was 58 years (SD=17.65). There was no significant difference related to age between those who were decannulated and those who were not (p=0.494).

Anxiety and Decannulation Outcomes

Of the 44 patients, 37 completed anxiety questionnaires. Of the 7 who did not, 3 patients were non-communicative, and 2 patients were in delirium. Of the 39 patients that were successfully decannulated, 34 completed the STAI-6. Their mean STAI score was 10.97 (SD=4.06). Of the 5 patients that were not successfully decannulated, 3 completed the questionnaire. Their mean score was 9.7 (SD=1.16, p= 0.588), indicating there was no significant difference related to anxiety between groups.

GCS and Decannulation Success

Of the 39 patients that were successfully decannulated, the mean GCS was 14.8 (SD=1.02), whereas the mean GCS was 12.6 (SD=3.29) for those 4 who were not successfully decannulated. There was a statistical significance between those who were successfully decannulated and those who were not in relation to their GCS score (p = 0.002).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the MUHC capping trial protocol in facilitating tracheostomy decannulation. By examining the number of patients successfully decannulated following the capping trial, and considering various clinical factors that may impact outcomes, the results offer important insights into the protocol’s performance and potential areas for improvement.

Success of the Capping Trial Protocol

The results indicate that the MUHC capping trial protocol facilitates decannulation, with a high decannulation success rate of 89%. Most patients (87%) required only one trial attempt, highlighting the efficiency of the protocol for the majority of patients. This outcome suggests that the capping trial is a robust and structured approach for determining decannulation readiness in patients with tracheostomy tubes. However, it is worth noting that some patients did require modifications to the standard trial protocol, including extended or accelerated capping trials, indicating that the protocol is adaptable to individual patient needs. The flexibility of the capping trial, allowing for variations in the timeframe based on patient conditions, is a strength of the protocol. The study also highlights that 11% of patients were not successfully decannulated, which underscores the importance of ongoing monitoring and individualized care for patients undergoing the capping trial. The reasons for failure included respiratory distress and an inability to manage secretions, which are critical factors to determine if the patient can be decannulated.

Influence of Age on Decannulation Outcomes

The study found no significant difference in age between patients who were successfully decannulated and those who were not. This result suggests that age is not a major determinant of success in the capping trial protocol. Previous studies have shown mixed results regarding age as a factor in decannulation success, with some suggesting that older age may be associated with lower success rates.21 However, our study aligns with the findings of other studies that did not find age to be a significant factor.22

Anxiety and Decannulation Outcomes

Anxiety levels, as measured by the STAI-6 questionnaire, were not significantly associated with decannulation success. While it might be hypothesized that anxiety could hinder a patient’s ability to successfully complete the capping trial due to its potential effects on breathing patterns or compliance with the trial protocol, this study did not find such a correlation. However, it remains important to address anxiety in clinical practice, as it can affect patient comfort and cooperation, even if it does not directly influence clinical outcomes.

Glasgow Coma Scale and Decannulation Success

In contrast to anxiety, the GCS, was a significant indicator of decannulation success. Patients who were successfully decannulated had a higher mean GCS score compared to those who were not decannulated. This finding is consistent with the well-established notion that a higher level of consciousness is essential for the patient’s ability to manage their airway and secretions,21–26 both of which are critical components of the capping trial. Patients with lower GCS scores may be at greater risk for respiratory complications or difficulty clearing secretions, which could explain why they were less likely to successfully be decannulated.

This result highlights the importance of closely monitoring patients’ neurological status when considering them for a capping trial, as those with impaired consciousness may require additional interventions or prolonged monitoring. It also suggests that GCS could be a useful tool for tracheostomy teams in determining decannulation readiness.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

One significant limitation of this study was the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on recruitment, which resulted in a smaller sample size and possibly a selection bias. The pandemic affected the availability of eligible patients potentially limiting the generalizability of these findings. Furthermore, the observational nature of this study means that causality cannot be established, and future randomized controlled trials would be valuable to confirm the findings and explore other potential factors influencing decannulation success.

Additionally, although this study included an assessment of anxiety, other psychological factors, such as depression or coping strategies, were not measured but may contribute to a patient’s ability to undergo the capping trial successfully. Future research could expand on these psychological factors and explore how they might influence outcomes. The findings of this study may also not be generalizable to other countries or institutions, as it was conducted at a single hospital site. Lastly, the study did not assess long-term outcomes post-decannulation, such as reintubation rates or the need for further respiratory interventions. Longitudinal studies would provide more insight into the long-term outcomes of the capping trial protocol, as well as its impact on patient quality of life. However, for this study, there were no instances of decannulation failure whereby a patient required the reinsertion of a tracheostomy tube 24-48 hours post decannulation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the MUHC capping trial protocol appears to be an appropriate method for facilitating tracheostomy decannulation, with a high success rate and a structured process that can be adapted based on individual patient needs. While factors such as age and anxiety had no significant correlation with decannulation success, GCS was found to be a strong indicator of outcomes. These findings contribute to the growing body of knowledge on capping trials and highlight the importance of personalized care in the management of tracheostomy patients. Further research is needed to explore additional factors influencing decannulation success and to assess the long-term outcomes for patients post-decannulation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study participants for their courage and willingness to assist with the study, as well to the following members of the research team.

Assistance with the study

Melanie Giroux, RRT, Respiratory Therapy Department, Multi-Disciplinary Services Directorate, McGill University Health Centre

Ruth Guselle, RN, BSN, Intensive Care Unit, Surgery Department, McGill University Health Centre

Maude Brisson-McKenna, MSc. (A), S-LP, Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology Department, Multi-Disciplinary Services Directorate, McGill University Health Centre

Financial support and sponsorship

This Small Grant Nursing Research study was made possible because of the generosity of the Newton Foundation, with matching funds from the Montreal General Hospital Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

None.