Introduction

Acute care of patients with a tracheostomy is high risk with significant associated morbidity and mortality requiring specialist expertise to manage.1,2 There is recognition that best practice tracheostomy care requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach to standardize care and improve safety within this patient population.3–6 Implementation of interprofessional tracheostomy care results in reduced frequency of adverse events, decreased time to decannulation and shorter hospital length of stay with associated health cost savings.1,6,7 Other benefits include junior staff education, training and support.8,9

The importance of coordinated care of patients with a tracheostomy is widely recognized and a key component of the Global Tracheostomy Collaborative.4,10 While it is well established that an interprofessional approach is required for patients with a tracheostomy, recommendations on the structure of the team and service model, including frequency of meetings and when a tracheostomy team review should be initiated, are not clear.11,12

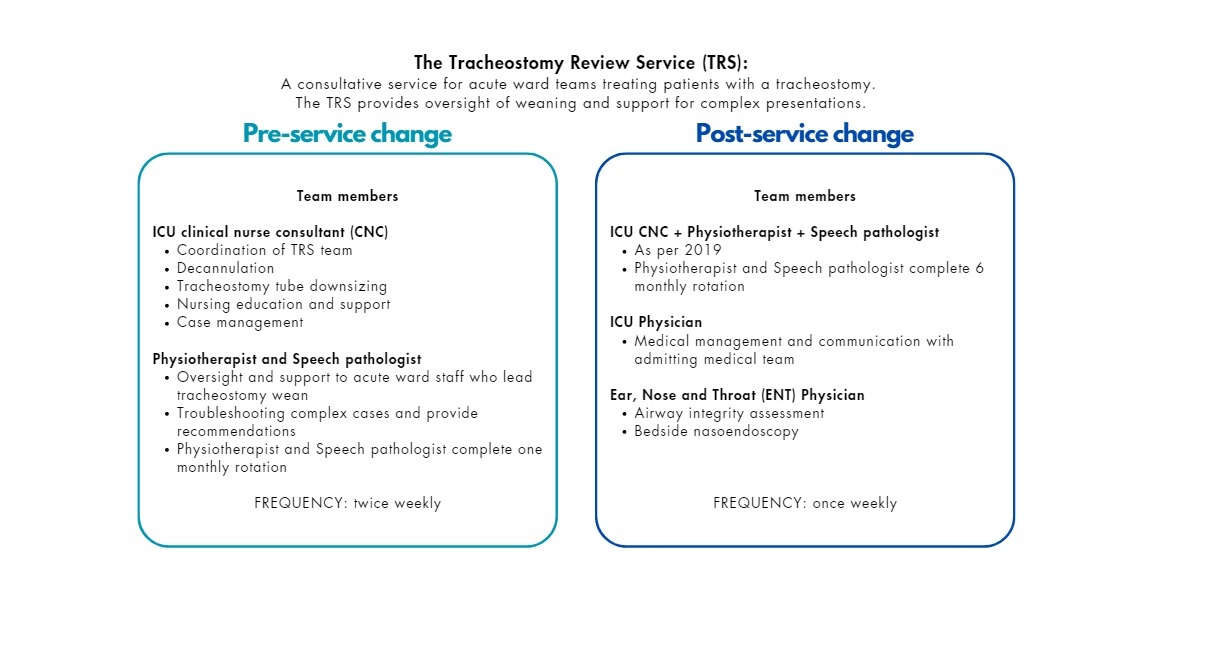

The Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH) established an interprofessional Tracheostomy Review Service (TRS) in 2001. Originally, the service did not have consistent specialist medical input. The TRS had representation from an Intensive Care Unit clinical nurse consultant (ICU CNC), rotating senior speech pathologist and rotating senior physiotherapist. On twice weekly ward rounds, the TRS reviewed all patients with a tracheostomy (excluding those in the intensive care unit or admitted under the Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) team), with a goal of consulting on tracheostomy weaning, cuff management and tracheostomy tube changes including downsizing. A survey was disseminated to staff treating patients with a tracheostomy following a local audit of TRS patient medical note documentation in 2019 which revealed inefficiencies in the service, for example inadequate documentation of tracheostomy weaning plans. Facilitated by an ICU Medical Consultant, a revised model of care was implemented shortly after. The new model of care in 2021 included additional team members and the frequency of the TRS was reduced to once weekly. Figure 1 portrays the TRS model of care in 2019 and 2021 with team member roles explained. The aim of this study was to evaluate staff perspectives of the TRS pre and post implementation of a new model of care including clinical utility and defining the primary roles of the TRS.

Methods

Ethical approval for this study (QA2020110) was provided by Melbourne Health Office for Research on 14 July 2020. This study is reported according to the Checklist of Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS), (See Supplementary file E1 for full checklist).13 A survey pre and post implementation of a new model of care evaluating the TRS service was completed in a tertiary hospital in Melbourne, Australia. The new model of care, which began in 2019, consisted of the inclusion of permanent specialty medical staff (ICU and ENT) in the TRS and consistent senior speech pathology and senior physiotherapy team members. At the once weekly interprofessional meeting, the TRS completed both review of patient records and bedside assessment. On the wards, tracheostomy cuff deflation trials continued to be led by the ward-based physiotherapist and speech pathologist who had completed discipline specific competencies.

The 2019 pre-implementation survey comprised of 23 items with an additional two questions in the post-implementation survey to evaluate staff perceptions about the impact of the change in model of care (See Supplementary file E2 for full survey). This was developed, piloted by the study team and administered via secure online platform REDCap. A convenience sample of all senior physiotherapists, senior speech pathologists, ICU CNCs, nurse unit managers and associate nurse unit managers on six wards that receive non-ENT patients with a tracheostomy (intensive care, trauma, general medicine, respiratory, neurosurgery and stroke/neurology) were invited to participate. Senior physiotherapists and senior speech pathologists are denoted as staff in positions above entry level (Grade 2 or above), usually have at least two years of clinical experience in their profession and have completed discipline specific tracheostomy management competencies. Staff were identified via email distribution lists and were sent a singular email to complete the online questionnaire. The sample was chosen based on their involvement with patients with a tracheostomy serviced by the TRS or their involvement in the TRS. There were no specific exclusion criteria. The survey was open for two weeks at both timepoints; November 2019 and February 2021. Completion of the survey implied consent of participating in the study. Accounting for changes in staff over the survey period, the surveys were not paired.

Questions collected demographic data including discipline, years of experience at the organization and years of experience caring for patients with a tracheostomy and explored perceptions of the TRS model of care including utility, primary roles, efficacy, and suggestions for improvement.

The survey responses were only accessible to the study team. They were stored on REDCap, de-identified, extracted and analyzed in Microsoft Excel and/or SPSS Version 28. Incomplete surveys with any TRS evaluation questions completed were included in the results. Demographic data and categorical TRS evaluation data were summarized via number and frequency. To analyze central tendency, 5-point Likert scales and adverbs of frequency were converted to scores where 1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree and 1=never, 5=always respectively. They are reported as descriptive statistics via medians and interquartile ranges. Reflective thematic analysis14 was used to analyze the qualitative survey data (questions 3, 6 and 7 from Supplementary File E2). Two independent physiotherapists performed the analysis with a third physiotherapist assisting with any conflicts.

Results

In 2019, 37 unique surveys were fully completed with most responses from physiotherapists (46%). In 2021, there were 30 survey responses (two partially completed with demographic questions only therefore were removed from the analyses) and the majority of respondents were nursing staff (53%). Table 1 summarizes the demographic data for both surveys.

Overall, the median rated effectiveness of clinician time during TRS rounds in 2019 was 3.0 [2.0 - 4.0] and in 2021 was 4.0 [3.0-4.0]. Staff also rated the new model of care a median score of 4.0 [3.0 - 4.0] as an improvement to 2019.

Table 2 presents the median scores for usefulness, timeliness of recommendations, appropriateness of the frequency and duration of the TRS, and the suitability to decannulate patients on Friday prior to the weekend when there are less staff rostered. Amongst the list of primary roles that the TRS was intended to undertake, the top three roles reported by staff in 2021 as “quite” or “very” important were: making new recommendations regarding tracheostomy management (93.1%), providing alternative management plans to that of the main hospital medical team (89.7%) and liaising with other clinical teams (89.6%) (Table 3). In relation to the frequency of the TRS, 59% of respondents in 2019 indicated the service should operate on a referral or ‘as needed’ basis. After reducing the service to weekly, 52% of respondents in 2021 reported the service should continue to run weekly.

Themes identified from free text questions are summarized in Figure 2 and are presented with supporting quotations in Supplementary File E3 Tables 1-3. There were seven barrier themes and four improvement themes in 2019 and three barrier themes and three improvement themes in 2021.

Barriers to the implementation of TRS recommendations

In 2019, a lack of consensus between team members was a major theme, particularly for patients that had multiple staff teams managing their tracheostomy weaning plan.

“The home [main hospital] medical teams do not appear to act on trache[ostomy] round recommendations.”- Physiotherapist 15, 2019

This was an ongoing theme in the 2021, where respondents suggested that the teams may have opposing recommendations, or the main hospital medical team involved in the patient’s care may ‘pushback’ the TRS’ recommendations.

Poor communication between the TRS and the main hospital medical team was also reported in both surveys. However, in contrast, in 2021 this was more focused on the optimization of electronic medical records.

“Tracheostomy documentation needs to be optimised in [electronic medical records]!!!!”- Physiotherapist 4, 2021

Staff highlighted that CNCs were unavailable to attend the TRS if there was a concurrent medical emergency team (MET) call which resulted in cancellation of the TRS service in 2019. However, in 2021, with the additional staffing, the TRS could run during MET calls with reduced ICU medical or CNC support.

In 2019, respondents also reported a lack of new recommendations by the TRS.

"The recommendations of the tracheostomy team are rarely any different to the management of the treating clinicians so often there is little to add."- Speech pathologist 4, 2019

Suggested improvements for the TRS

There were three improvement recommendation themes in both the 2019 and 2021 survey. Improving communication was a theme in both surveys, with proposed strategies including liaising with the ward nurse in charge and clear documentation of recommendations.

“Reliance on ward nurses to relay the recommendations, maybe it should be communicated to the nurse in charge.”- Nurse 9, 2021

In 2019, respondents called for a change in service provision including the evaluation of the TRS and flexibility in frequency of consults for specific patients. This was echoed in 2021, that some patients may have more need for the TRS than others.

“[Is it] suitabl[e] for more complex patients to be seen twice a week, and more straightforward patients once a week?”- Speech pathologist 2, 2019

The need for specialist teams and consistent experienced TRS staff was identified in the 2019 survey. This included a recommendation for an increase in medical support and senior skilled clinicians.

“I would like the service to have really senior or specialist clinicians that can troubleshoot any trache[ostomy] … Sometimes it feels like trache[ostomy] review service is a data collection service rather than providing recommendations, surveillance of trache[ostomy] practice, teaching and development opportunities.”- Physiotherapist 11, 2019

Lastly, the role of the TRS to provide education was emphasized in 2021 particularly for junior clinicians.

“It would be great if they helped nursing education and communicated so everyone on same page. Currently no clear education/training plan used through the whole hospital. Every ward is trained differently and no consistency.”- Nurse 10, 2019

Perspectives on the new model of care from 2019 to 2021

Respondents described themes of improved efficiency and format, and design resulting from the new model of care (Supplementary file E3 Table 3).

“The trache[ostomy] review service is a complimentary adjunct to routine tracheostomy management for some patients.”- Speech Pathologist 5, 2021

“More efficient, providing appropriate care with fewer resources.”- Physiotherapist 5, 2021

However, some responded that the service had no additional value to the care of patients with a tracheostomy over the main hospital medical team due to the ward team’s skillset.

"Senior staff Nurses [on ward] are well trained in managing trache[ostomy] together with AH and ENT so we don’t need much assistance from trache[ostomy] services.''- Nurse 15, 2021

Discussion

Whilst our hospital had an existing TRS in 2019, staff responsible for the care of patients with a tracheostomy reported an appetite for improvements in service delivery and patient care. A recent systematic review investigating the effectiveness of tracheostomy teams found that an interprofessional approach improved patient safety, time to speech therapy consultation, time to decannulation and reduced hospital LOS.15 What is less known is how best to run this service in terms of its team members, role and frequency.

The team members that make up the TRS can be limited by factors such as funding, the type of health institution and country of origin.15 Across different countries, specialty disciplines can have different roles making it difficult to create a ‘core’ team.15 A recent systematic review investigating the effectiveness of interprofessional tracheostomy teams reported across all 14 included studies that tracheostomy teams included a physician and clinical nurse specialist/medical resident.15 This physician was an intensivist or anesthesiologist, ENT surgeon, respiratory doctor or general surgeon. A speech pathologist was included in 13 services and a physiotherapist was included in 11.15 This aligns with our TRS, with the inclusion of specialized medical attendance in the new model of care. The addition of ENT clinicians has been particularly well received as they are able to perform fibroscopic nasoendoscopy assessments during patient reviews. This provides extended scope of the TRS and was perceived to provide a timelier response to the main hospital medical team’s concerns and to facilitate decannulation. A further strength of our new model of care is consistent attendance by appointed senior team members on weekly ward rounds, enabling continuity of care for the patient. Inconsistent team members have been found to be a barrier to implementing a tracheostomy team.15

Other team members that may be of value include dieticians for nutritional input, occupational therapists for functional performance, psychologists for management of stress and anxiety associated with a tracheostomy11,15 and family or friends to advocate for the patient’s needs. The effectiveness of these other roles within the tracheostomy team is less known and would be interesting to evaluate in future work.

The interprofessional tracheostomy team functions to improve patient safety and care.3–6 Their roles include weaning from mechanical ventilation in the ICU setting,7 tracheostomy changes or downsizing, early cuff deflation and facilitating decannulation on the wards,8,10,16 improved use of one way valves,7 management of adverse events, creation of policies, protocols and staff competencies.5 Our staff perceived the TRS’s main roles should be liaising with other teams, making new recommendations on tracheostomy management, providing alternative plans and facilitating decannulation (Supplementary file E3 Table 3). This information can be used to better define our service and the roles our team should focus on.

Additionally, of evolving importance is the provision of education to ward staff by the tracheostomy team to improve ward-level confidence with tracheostomy management and implementation of recommendations.5,9 This was mentioned only by a few participants in 2019, however was a theme in 2021. This may be due to an improved perception of the updated TRS in terms of specialist clinical attendance demonstrating an opportunity for education. Further extending the scope of the TRS may improve staff satisfaction and confidence in management of the patients with a tracheostomy. This is supported by a recent quality improvement project by Twose et al., 2019 which found that a dedicated tracheostomy team that provided staff education in addition to tracheostomy weaning, reduced adverse events and increased self-reported confidence in tracheostomy management.9 Staff education included tracheostomy study sessions and simulation training, completion of competencies and clinical support to staff and patients.9 This study also demonstrated improvements in time to decannulation and hospital length of stay, however these were not statistically significant.9

The 2021 survey highlighted that staff had ongoing conflicting feelings about the frequency of our TRS despite the change in model of care. While approximately half the survey respondents wished for consistent weekly interprofessional rounds to continue to ensure patient plans were actioned, others felt it should occur as needed. There is little consensus as to how frequently a tracheostomy service should run; some services run daily providing all tracheostomy related care,17,18 others run once to twice weekly via ward rounds, with weekly being most common.4,8,9,19,20 Many publications do not mention frequency of review.2,10

To our knowledge, there is no evidence on how frequently an interprofessional tracheostomy round should occur to provide optimal patient care. It is likely that the ideal frequency of the service relates to specific hospital needs, patient population and staff experience.

Our new model of care included specialized medical input, consistent speech pathology and physiotherapy presence and reduced ward rounds to once weekly from twice weekly. Redesigning the format of the TRS resulted in an improvement in staff perception of an efficient service. Challenges remained regarding documentation and communication from the TRS to other team members. Our hospital service implemented a new electronic medical record (EMR) system in August 2020 and staff may still have been familiarizing themselves to the system during the post implementation survey period. Anecdotally, this has improved with the implementation of pre-populated note templates within the EMR with a section for each discipline of the TRS to input.

Our survey included respondents from various clinical backgrounds, with differing tracheostomy experience. The prospective, pre and post design allowed exploration of the impacts of a new model of care based on staff feedback. Of note, pre-implementing service changes in 2019, the previous model had run from 2001 to 2019. Our new model of care had only been established 2 years prior to re-evaluation, which may have influenced responses. This study outlines components of an effective TRS, including describing service roles, meeting frequency and team membership. Study limitations include that the survey was not circulated to specialty medical staff (ICU and ENT), so we were unable to gain their opinions and perceptions of the TRS. The email distribution lists have also subsequently changed; therefore, we are unable to determine the response rate for either survey timepoint. To investigate the perspectives of staff in more depth, a focus group or interview study could be considered. Additionally, no patient-related outcome measures were gathered in this study, therefore any potential impacts on patient outcomes are unknown.

Future opportunities include investigating patient outcomes, such as time to decannulation, complications and patient experience, as well as expanding the TRS service to include staff education resources to optimize tracheostomy management. It would also be beneficial to gain insight from specialty medical staff to determine what they feel is important and valuable to the TRS. Further investigation regarding verbal and documented communication challenges would be of benefit. There remains support for trialing a referral only based service delivery model.

Conclusion

Key gaps were identified in the TRS service affecting efficacy. The 2021 new model of care including ENT and ICU physician expertise in addition to the existing ICU CNC, Physiotherapist and Speech pathologist team members enhanced the expertise of the interprofessional team. The TRS also ran less frequently but also had more consistency with Physiotherapy and Speech pathologist members. Staff perceptions of usefulness and effectiveness of TRS improved through the additional of specialty physician support and service re-design to facilitate improved tracheostomy care.

Financial support and sponsorship

none

Conflicts of interest

none

Presentations

-

International Tracheostomy Symposium 2023: The Global Tracheostomy Collaborative: Building the Future of Tracheostomy Care: Baltimore, USA

-

Australian Physiotherapy Association IGNITE Conference 2023: Brisbane, Australia