Introduction

Pediatric tracheostomy, among the most common procedures performed on critically ill patients, is associated with high morbidity and mortality, with complication rates ranging from 12.6%-30%.1–5 Deficiencies in the understanding of tracheostomy tube care among non-otolaryngology healthcare providers who routinely care for these patients is widespread.6–13 This is recognized as a pervasive and multi-faceted problem globally, and effective standardized education of healthcare providers at every stage of training is a key driver of successful quality improvement efforts in tracheostomy care.13 Single modality educational interventions have been implemented to improve provider knowledge, skills, and confidence with tracheostomy management,13–24 however, slow dissemination of best practices in tracheostomy care remains a major barrier to widespread quality improvement efforts.13,25

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has accelerated the use of online and video-based learning modalities in healthcare training.26–34 Online modules are available on-demand, can be completed at the individual learner’s preferred pace, and can be disseminated to larger groups with less resource expenditure than in-person training. While virtual learning modalities are shown to be feasible for teaching tracheostomy skills, the learning style is more passive than live hands-on, in-person sessions, which allow demonstration and correction of skills.25 Live video sessions strike a balance between online modules and in-person sessions, providing a more active learning style with the opportunity to ask questions and receive feedback in real-time; however, suboptimal hardware and audio/visual display can present challenges for hands-on skills training, especially in resource-limited settings.25

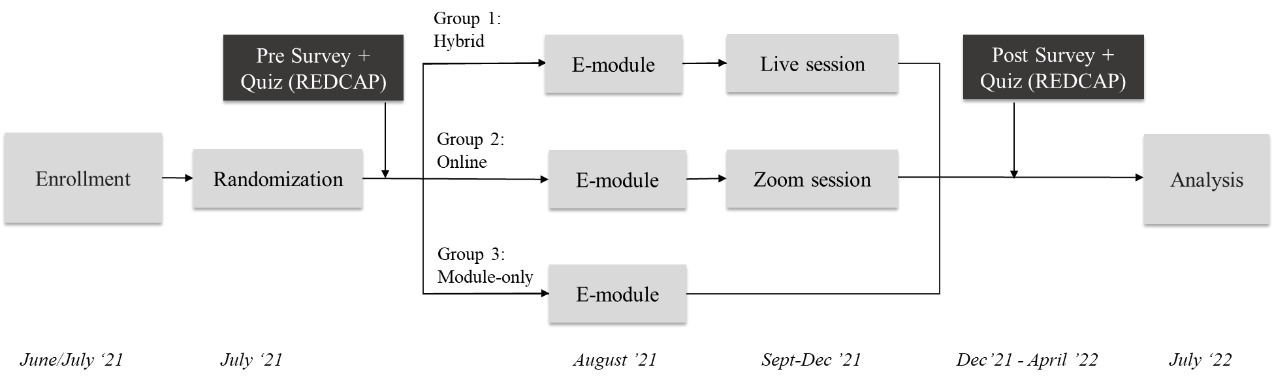

The goal of our study was to pilot a multimodal pediatric tracheostomy curriculum in a single tertiary care pediatric residency program. Our primary objective was to study curriculum completion for three study arms 1) online module plus in-person training (hybrid), 2) online module plus video training (online), or 3) online module only (module only). Our secondary aim was to compare (a) self-assessed confidence with tracheostomy care and (b) scores on a tracheostomy care knowledge quiz, stratified by study arm and PGY-level.

Methods

Setting and participants

This study was conducted on pediatric residents at a tertiary care children’s hospital during the academic year July 2021 - June 2022.

Randomization Model

Participant data including study identifier (ID), year in training (post-graduate year (PGY)-1, 2, or 3), sex, prior experience with tracheostomies, and resident schedule (specifically, whether each resident had completed 0, 1, or 2+ ICU rotations) was input by a member of the research team into a random allocation model in Microsoft Excel (MS Office, 2021). Participants were stratified by each of these categories, then allocated into their final assigned study arm based on a random number assigned to them.

Interventions

Residents were randomized to one of the three study arms: hybrid, online, and module only. The hybrid group was assigned to an online pediatric tracheostomy care module and a hands-on training session with faculty (one hour: 10-minute lecture, followed by skills session with a low-fidelity tracheostomy mannequin with informal question-and-answer). The online group was assigned the online module and a live video-conference session (one hour: 10-minute lecture, followed by skills session on Zoom© with identical low-fidelity tracheostomy mannequins and equipment for learners and instructor with informal question-and-answer). The module-only group was assigned the online module with no additional training session.

Sequence

The timeline of the study is depicted in Figure 1. A previously tested online pediatric tracheostomy care module was assigned and distributed to all pediatric residents electronically via our institution’s intranet-based online education management system in August.35 The module comprised of an interactive slide format with audio instruction and audio-visual scenarios.

Live in-person and video hands-on training sessions were conducted during Academic Half Day, one afternoon per week of protected educational time in the pediatric residency program. Participants were assigned to complete a survey and 10-question quiz at the beginning of the academic year and again after training. The survey and quiz were adapted from our team’s prior study,35 with questions added to tailor the instrument to pediatric residents post-pandemic. Specifically, we gathered data on each resident’s number of prior PICU and NICU rotations, where they are most likely to care for patients with tracheostomies, and any prior experience caring for Covid-19 patients with tracheostomies. Surveys and quizzes were distributed via REDCap directly to participants’ institutional emails. Data was de-identified prior to analysis.

Instruments

The survey included self-assessment of confidence on a 5-point Likert scale six items: recognizing proper tube position, recognizing obstruction, suctioning, tracheostomy tube changes, responding to accidental decannulation of a mature tracheostomy tube, and responding to accidental decannulation of a fresh tracheostomy tube. In addition, the survey queried participants’ previous clinical experience caring for patients with tracheostomies. The 10-question multiple-choice quiz (10 points per question for maximum score of 100) evaluated understanding of tracheostomy tube size, type, bedside equipment, suctioning technique, cuff management, and responses to tracheostomy emergencies.

Outcomes measured

Feasibility (curriculum completion rates), acceptability (learning modality preference as indicated in survey), change in provider confidence (Likert scale survey responses) and knowledge (quiz scores) were assessed by study arm and PGY-level.

Analysis of outcomes

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software, version BE 17.0 (Copyright 1996–2021, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Data was examined for normality (using visual inspection of histograms) and equal variance and analyzed using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, interquartile range) for baseline data. ANOVA was used to evaluate curriculum completion rates, baseline pre-test confidence and quiz scores by study arm (per-protocol analysis) and PGY-level. Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. For the 29 participants who completed both pre- and post-assessments, paired t-tests were used to assess change in confidence (Likert scale)36 and quiz scores (α=0.05). A complete case analysis approach to missing data was used, and participants with missing survey and quiz data were omitted from analysis.

Ethical Considerations

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the IRB approval number was 2018-9184.

Results

Demographics and summary

Eighty-five pediatrics residents were enrolled in this study (Table 1).

Among them, 29 were PGY-1 (34.1%), 29 were PGY-2 (34.1%), and 27 were PGY-3 (31.8%). 68 participants (79.1%) were female. At the beginning of the study period, 29 participants were assigned to the hybrid study arm, 30 to the online study arm, and 26 to the module-only study arm; 3 residents from the hybrid group and 8 residents from the online group crossed over to the module-only group due to inability to attend live or video sessions, resulting in a final allocation of 26 residents in the hybrid study arm, 22 in the online study arm, and 37 in the module-only group. Final study arm groups were similar in makeup by PGY level, gender, number of residents with prior tracheostomy care experience, baseline survey responses and quiz scores. Baseline survey and quiz data are summarized by study arm in Table 2 and by PGY level in Table 3.

Curriculum and survey completion rates are summarized in Table 4. Online module completion was 11.8% overall and did not differ significantly by study arm (p=0.36) or PGY-level (p=0.06). Survey completion rates were similar across all study arms (p=0.38) and PGY-levels (p=0.42). Fifty-seven residents (67.1%) completed the pre-training survey, 41 (48.2%) completed the post-training survey, and 29 (34.1%) completed both the pre-training and post-training surveys. The mean change in survey and quiz scores among participants who completed none or only part of their assigned curriculum is summarized in Table 5. Across all study groups, post-module surveys found that 39/41 participants (95.1%) preferred live, in-person training and 2/41 participants (4.9%) preferred training via Zoom.

Confidence

Post-module surveys demonstrated a significant increase in mean confidence (1.3±0.9, p<0.001) overall and with regards to each of the 6 items. There was a greater mean increase in confidence in the hybrid (1.8±0.5, p<0.001) and online (1.9±0.9, p<0.001) study arms than in the module-only study arm (0.6±0.7, p=0.03). There was also a greater increase in mean confidence among those who completed part or all of their curriculum (1.3±1.0, p<0.001) than among those who did not complete any part of their curriculum (0.7±0.7, p=0.02). A mean increase in confidence was also observed among PGY-1 residents (1.6±1.0, p<0.001), PGY-2 residents (1.5±0.6, p<0.001) and PGY-3 residents (0.9±1.0, p=0.01) (Table 5).

Knowledge

Quiz scores increased from a mean of 61.0% on the pre-training quiz (n=57) to 72.2% on the post-training quiz (n=41) (11.2%, [CI 4.0%, 18.4%], p=0.003). The most common questions answered incorrectly in the pre-training quiz were identifying the purpose of an obturator (75.9% incorrect responses) and identifying an obturator in an image (77.6%). The most common questions answered incorrectly in the post-training quiz were identifying an obturator in an image (68.3%) and selecting the appropriate depth of suction catheter insertion (70.7%). In paired analysis (n=29 learners who completed both the pre- and post-quizzes), knowledge improved among those who completed all or part of their curriculum (1.7±0.8, p<0.001), those in the online study arm (14.4±16.7%, p=0.03), PGY-1s (19.0±1.67%, p=0.006) and PGY-2s (21.2±21.0%, p=0.02) (Table 5).

Discussion

Novel findings

This study is novel in its assessment and comparison of three different modalities of tracheostomy training in an urban, academic tertiary medical center system pediatric residency program. Capitalizing on the potential of live video skills sessions for training of large groups of learners, these curricula could be applied broadly with lower resource investment. Completion rates and increase in confidence were similar among those who received live hands-on training sessions held either in-person or over Zoom, and these modalities demonstrated a greater mean increase in confidence scores for participants.

Feasibility

The main feasibility challenges encountered during the study were low module completion rates, and scheduling and attendance for both the hands-on live and video training sessions. Module completion rates were low across all three study arms including the module-only group, likely due to limited accessibility of the intranet-based module for learners on ambulatory rotations. As a result, the module-only study arm acted more as a control group than an assessment of a third modality of education.

All participants in the hybrid and online study arms attended either the initial training session during Academic Half Day in September 2021 or one of four makeup sessions scheduled between October and December to meet our goal of educating as many residents as possible with equal proportions of PGY-level per study arm group. The initial sessions in September had the highest attendance (15-20 learners per hands-on live in-person and live video groups), while attendance at subsequent makeup sessions was limited due to scheduling conflicts with other educational objectives and clinical duties. Ultimately, three participants in the hybrid study arm and seven in the online study arm were re-assigned to the module-only group due to inability to attend the initial training session or any of the makeup sessions, challenges we will seek to address by staggering small group live in-person training by 6- and 12-week rotation blocks across the current academic year.

Confidence and Knowledge

Overall, there was a significant increase in mean quiz score and mean confidence with tracheostomy skills after training. There was a greater increase in confidence among participants in the hybrid and online study arms than in the module-only study arm. We also observed higher average post-training quiz scores in the hybrid and online groups than the module-only group and a statistically significant improvement in quiz scores in the online group. These findings suggest similar effectiveness for live in-person and video training sessions. Mean increases in confidence and quiz score were greater among PGY-1 and PGY-2 residents than PGY-3 residents. These increases were anticipated in light of lower baseline confidence and quiz scores and less reported clinical experience caring for patients with tracheostomies in the more junior resident training levels.

Limitations

Limitations of our study include low survey completion and self-directed online module completion rates across all groups. Although we found a significant increase in tracheostomy knowledge, both when examining the 29 participants who completed the pre- and post-module quizzes and for the online study arm alone, there was no significant increase in tracheostomy knowledge for the hybrid group, likely due to small sample sizes and low post-survey response. Although our curricula had been developed and approved by a multidisciplinary team of tracheostomy experts and previously tested among other learner groups at our institution, there is no gold standard instrument for measurement of pediatric tracheostomy care knowledge. Although all residents assigned to the hybrid and online groups received education, not all residents who completed their assigned curriculum also completed both surveys. Through a complete case analysis, participants who did not complete both surveys were omitted from statistical analysis. Reduced statistical power due to this missing data and small sample size may have affected the study’s ability to detect meaningful differences between groups. Therefore, while no significant difference between the hybrid and online groups was detected, it is possible a difference would have been found with a larger sample of surveys. Also, although we found a significant increase in tracheostomy knowledge, both when examining the 29 participants who completed the pre- and post-module quizzes and for the online study arm alone, there was no significant increase in tracheostomy knowledge for the hybrid group, likely due to small sample sizes and low post-survey response. Crossover and possible non-random attrition of participants, which could have been mitigated by strict adherence to randomization or intention-to-treat analysis, might have affected the generalizability and internal validity of our findings. While these limitations may have negatively impacted the study’s generalizability, they also revealed potential barriers to education of residents and inspired future endeavors to improve participation and survey response rates.

Additionally, survey responses are subject to response bias, in which those who were more engaged or confident in their improvement were more likely to complete the post-training survey and vice versa. Survey responses are also subject to recall bias, whereby respondents may over- or underestimate how frequently they have encountered certain experiences with tracheostomy care. It is also possible that measures of self-assessed provider confidence may be subject to the Dunning Kruger effect, which occurs when individuals lacking knowledge and skills in a certain area may overestimate their own competence while individuals who excel in that same area underestimate their relative abilities.37,38 This may contribute to a potential misrepresentation (more likely to be an underestimate in this learner population) of the true impact of training. Though there is high face validity to the belief that our respondents would respond honestly and accurately, these data are unverifiable. Lastly, although our curricula had been developed and approved by a multidisciplinary team of tracheostomy experts and previously tested among other learner groups at our institution, there is no gold standard instrument for measurement of pediatric tracheostomy care knowledge.

Future Directions

Results of this study indicated that training sessions were effective in increasing resident knowledge and confidence regarding tracheostomy care. However, low online module completion rates and scheduling conflicts indicated that regularly scheduled hands-on simulation sessions were necessary to ensure residents received training. The following academic year, all incoming first year residents attended a hands-on pediatric tracheostomy training session during orientation, while second- and third-year residents were assigned to simulation training sessions scheduled by rotation block throughout the year. These changes resulted in an increased the curriculum completion rate of 85.23% and ensured residents received tracheostomy education regardless of module completion.

Assistance with the Study

Megan E. McCabe, MD, Julia Komatsu, MD, Pediatric Chief Residents; Statistical consultation: Melissa Fazzari, PhD; Montefiore Einstein Center for Innovation and Simulation (MECIS); Montefiore Learning Network; Pediatric Airway Committee.

Financial support

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Clinical Research degree from the Clinical Research Training Program, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. This research was supported by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) Einstein Montefiore CTSA Grant Number UL1TR001073.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Presentation

Preliminary data was presented at Society for Ear, Nose and Throat Advances in Children (SENTAC) in Philadelphia, PA on December 3, 2022.

Corresponding Author

Christina J. Yang

Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery

3400 Bainbridge Ave

Medical Arts Pavilion 3rd Floor

Bronx, NY- 10467

Email: chyan@montefiore.org

Phone: 718-920-4267